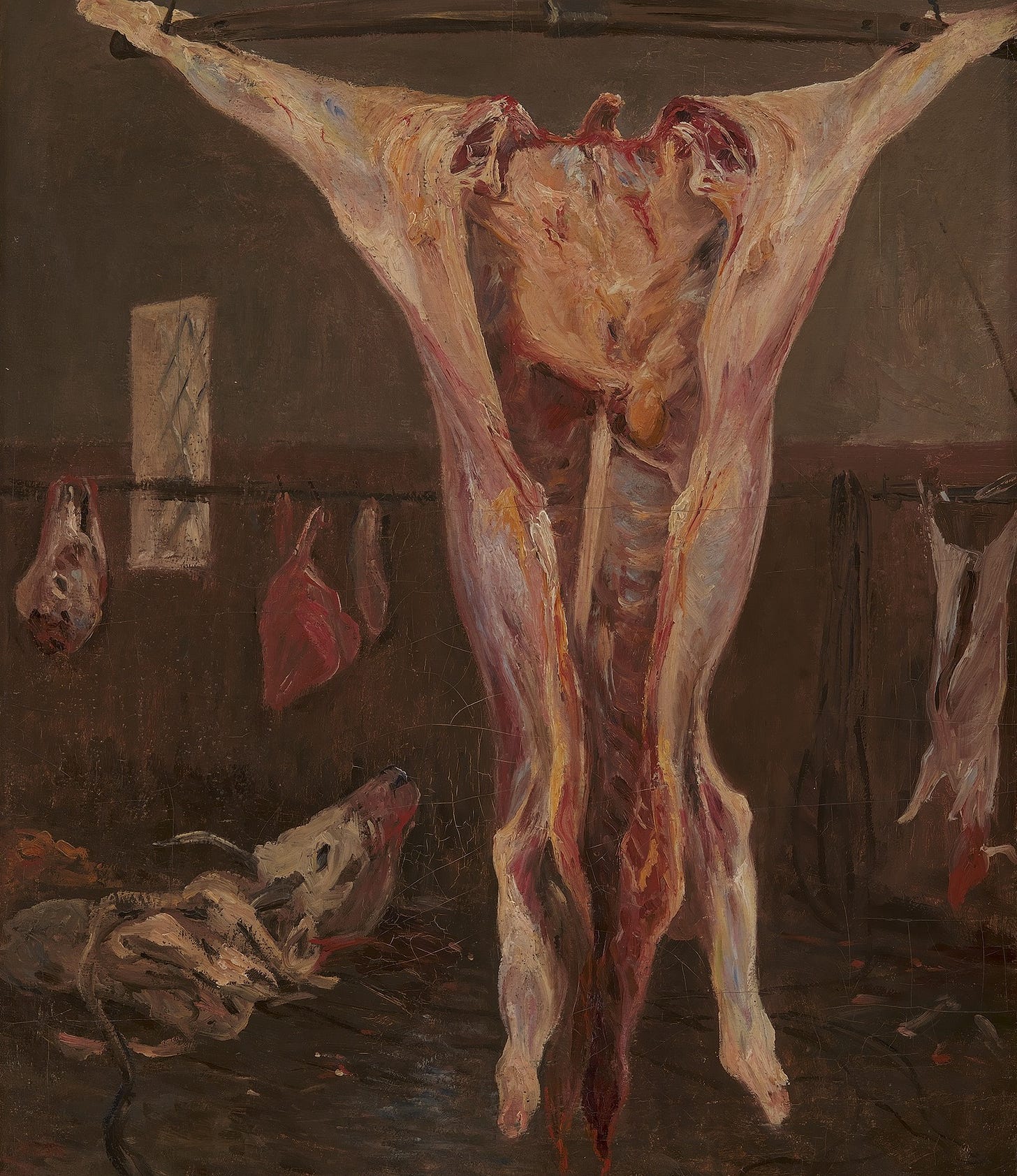

Ahh gold… The shank of the universe… Much like the butcher has cut the cow at the joints where it’s the easiest, so God—when creating the world—cut everything we see around us into nice neat categories: The natural kinds.

The idea of natural kinds is basically that there are some classifications of things—be they in terms of categorical essences, property clusters, or what have you—that are right or real. As suggested, these are supposed to carve the joints of nature, as opposed to unnatural or gerrymandered kinds like “red objects in this room” or “people who are not yet subscribed to Wonder and Aporia” (nudge, nudge).

But I think there’s no such distinction! Instead there are just some irreducible properties and/or powers of things (or what have you) at the fundamental level, and no way of categorizing these is more right than any other.1

The Basic Argument

My reason for thinking there are no natural kinds is that, well, we just have no reason to think that there are. If there were natural kinds, which exactly they were would make literally no difference to the world whatsoever.

If gold and silver are natural kinds, the things making up the two would do gold-stuff and silver-stuff respectively. But imagine now instead that gold isn’t a natural kind. Instead the natural kinds are sold and gilver. Sold is what we call gold below 20°C and what we call silver above 20°C—mutatis mutandis for gilver. What would the world look like then? Well the stuff that we would call gold and silver would still do what we call gold-stuff and silver-stuff respectively—that is, we would notice no difference whatsoever! In fact, I bet we would have textbooks and scientists using “gold” and “silver” to formulate their theories and write their textbooks, not “sold” and “gilver.”

Where the “joints of reality” lie make literally no difference to what actually happens. What actually matters is what reality is, not where it is carved up. This of course includes our beliefs about reality. It seems we have no way of knowing what the natural kinds are to begin with—after all, what we see, think, and believe would all have been the same regardless of where the joints lie, as it’s the things that the natural kinds are aggregates of that make a difference, not the aggregation itself.

Perhaps you’d respond that we don’t know about each natural kind directly—rather we know about the rules for what differentiates natural kinds from gerrymandered categories. But again, if these rules were different, what would the world look like? Nothing about what any kind did would change, and we would be none the wiser.

If we say that that’s just how we define “natural kinds,” then sure, do what you want, but that doesn’t tell us anything interesting about the world. Whether I’m right or the natural kinds-believer is right, all the same things would be true of the world. I’m happy to allow that you can stipulate the word “natural kind” to mean whatever you want.

So it’s not clear what difference natural kinds make to the world or our thinking. At the same time, there is a very good explanation for why we think in terms of the kinds we do, without reference to what kinds there are: It’s super practical! The reason we would still use “gold” and “silver,” were the natural kinds different, is simply that thinking in terms of these kinds is very practical, and makes it so that we need less cognitive resources for making predictions. But this is orthogonal to whether the natural kinds are real.

And most importantly, natural kinds don’t do anything to simplify our theory of reality. A believer in natural kinds still needs to posit the things making up the kinds. I’m happy with positing these. But on top, they also need to posit that there are actually real natural kinds. This is just unnecessary metaphysical fluff, and we’re just introducing things to our ontology for no reason! So if we have no reason to believe in natural kinds, and doing so would make our theory worse, then we just shouldn’t.

Some Arguments to the Contrary (and why they fail)

Seeing as my argument basically comes down to: natural kinds complicate our worldview while adding nothing, I should probably respond to some of the reasons people give for thinking natural kinds do do important theoretical work.

Induction

Perhaps the most common reason given for believing in natural kinds is that they allow for induction. For example, when I observe a bunch of glasses of water freeze at 0 degrees (celcius; I’m not a troglodyte), I can inductively infer that the next glass of water will also freeze at 0 degrees. But these glasses of water are also part of the gerrymandered kind “water or Absolut Vodka,” so can I also infer that my glass of Absolut Vodka will freeze at 0 degrees? No! Because vodka and water differ in relevant respects—namely they don’t form a natural kind, and so don’t allow for inference.

The problem with this argument, I think, is that it gets wrong what allow us to make inductive inferences like this. When we see a bunch of things with surface-level properties A also have surface-level properties B, that gives us good reason to assume that there’s some underlying properties or explanation for these two—or that something somehow connects the two. So when we see a new object with properties A, that gives us good reason to think that the underlying explanation is present, and thus that B will also be present. But this underlying explanation can cut across natural kinds—it just happens that what we call natural kinds are often formed around these underlying explanations, exactly because they allow us to make these inferences. Imagine:

You’re taking a stroll through a forest and see a burnt tree. Then you see another, and then another, and so on all in a big clump. But after walking past a bunch of these trees, a big boulder blocks your view, meaning you can’t see what’s behind it. Before looking, you make a guess about what the next tree will be like. What are you justified in thinking?

Surely you should think that the next tree you see is also burnt! But wait a minute, ”trees in this forest” is not a natural kind, yet you’re allowed to make inductive inferences about this gerrymandered kind. What gives? What gives is that the things you observe (trees being burnt) probably have some underlying explanation (there having been a fire or something). That allows you to infer something about the next member in the kind, regardless of whether it’s natural or not.

So what matters when deciding which kinds you may make inductive inferences about isn’t whether that kind is natural or not—rather what matters is whether the members of the kind share the relevant features for the inference, naturalness be damned!

Both I and the natural kinds-believer will presumably think that surface-level behavior supervenes on the underlying properties—the natural kinds believer just says that certain groupings are more real than others. But what actually explains why we can make the inference is the supervenience base, not the supervenient natural kinds, so I don’t see why we need to posit these supervenient properties as “real” at all!

Explanation

In one of his excellent posts, Both Sides Brigade gives an argument for why we need higher-level “program” explanations, rather than just low-level “process” explanations. This is not strictly an argument for natural kinds—so I’ll cut BSB all slack here—but I think it can be retrofitted as such.

Keeping with examples that are cool asf, imagine that you put a cup of water outside in 15 degrees °F *throws up 🤮* -10 °C. Obviously it’ll freeze. But what explains it having frozen? It can’t be the exact temperature, as had the temperature been different, it’d still have been frozen (as the temp would then have been -9.9 °C or something). Rather the explanation must be that the temperature is below freezing. That is, there seems to be a proverbial joint in nature here, and it’s only an explanation that respects these joints can be an explanation at all.

Sadly, I’ll have none of this! I mean, the argument has snuck everything in the backdoor!! By taking a higher-order phenomenon as the explanandum, you have already smuggled your conclusion into the setup. You need to assume that there’s something special about the category “frozen water” rather than “frozen or slightly-above-freezing water” in order to get your conclusion that there’s a “joint” around 0 °C—but no one who doesn’t already believe in natural kinds will grant that assumption, and so it isn’t gonna be a particularly persuasive arguments for why you should think there are natural kinds to begin with.

Obviously if you take some higher-order phenomenon as an explanandum, you’ll also need a higher-order phenomenon as an explanans. The explanation for why this stick is shorter than 8 cm (which is a very respectable length btw) won’t be it’s exact structure, as the structure could’ve been different and the stick still be shorter than 8 cm—but that doesn’t give us any reason to think that there’s something special about this length!

Role in Laws

Another supposed reason for thinking there are natural kinds is that they figure in our best scientific theories and laws. Something like gold and silver will be mentioned in our best theories, but sold and gilver won’t. Hence gold and silver are real in a way that sold and gilver aren’t.

But, I mean, we could really formulate all the same theories using “sold” and “gilver” as we could with “gold” and “silver”—it’s just that it’ll be less practical to do so. Saying something like “gold catalyzes oxidation reactions” (I know this isn’t a rigorous example, just a proof of concept) could be reformulated to “sold catalyzes oxidation reactions when below 20°C and gilver catalyzes oxidation reactions when at 20°C or above.” What categories we use doesn’t change what we can describe, just how we need to formulate the description.

Sure, it’s easier to use gold and silver in the actual world. But what’s the inference supposed to be here? Using gold and silver is easier… so? They’re more real? If “gold” and “silver” are swapped with “sold” and “gilver,” and the rest of the theory is changed accordingly, the two ways of formulating the theory will say exactly the same things, and describe exactly the same worlds—nothing substantive is gained or lost.

Natural Kinds Externalism

Let’s finally consider Putnam-style natural kinds externalism. The idea here is that the content of our concepts goes beyond our mental states, and might depend on what goes on outside our heads—more specifically, our concepts often have natural kinds as their contents, whether or not we’re aware. The canon illustration of this is twin earth.

On earth water is H₂O, but imagine a planet—twin earth—identical to earth, except that water was really a distinct chemical compound XYZ. Up until the 19th century, earthlings and twin-earthlings would be in the exact same position for all they knew, and someone teleported between the two wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

Still, when twin-earthlings use the word “water,” it doesn’t seem like it means the same as when we use it—their “water” means XYZ, while ours means H₂O. So the content of our concepts isn’t determined by our mental states, and something about the external world—namely the natural kinds—also plays a role. Hence we need natural kinds to make sense of our concepts and mental content.

A first-pass response to this might sound similar to my point about induction: We can still have our contents be external, but rather than being natural kinds, they have as their content whatever the underlying structure causes the surface-level properties we’re aware of. So we can still get externalist content without natural kinds.

However, I don’t think this will be satisfying to the proponent. After all, it isn’t strictly H₂O that’s the underlying structure, but H₂O + dissolved minerals + tardigrades + bacteria + dirt, etc. Hence we can’t get the “clean” content that we want—namely H₂O simpliciter.

Here I’m gonna mirror my point about explanation: You’re already presupposing what’s at issue here! What we’re disputing is exactly whether H₂O is special to begin with, so by presupposing that we need to get H₂O as the referent, you’re smuggling in the conclusion!

Alas, the proponent probably won’t be satisfied. For the argument isn’t supposed to start from premises a dissenter already agrees with, and then force them to accept the conclusion. Rather it’s an intuition pump: Surely!—Surely there’s something special about H₂O here! What could be more obvious than that it’s true that “water”—even in the 18th century—means H₂O, not whatever hodgepodge you’re suggesting?

Finally, then, I’ll press on this feeling of specialness. My debunking argument from the beginning exactly cites this feeling of specialness as the debunking explanation. It’s obvious that we’d come to believe H₂O to be special once we start doing chemistry, as H₂O draws some distinctions and carves out lines in conceptual space that we’re interested in when doing science—so it’ll be counterproductive to focus on an alternative kind.

But what is special depends on which properties we’re worried about. If we’re worried about polarity, capillary forces, and electrolysis—as we are in the scientific enterprise—then it makes sense that we’ll abstract away these other features. But if we care about getting sick, or what’s gonna clog our coffee machines, it makes sense to include calcium and bacteria in what we call water. And I don’t think we can infer from this that the kinds we feel are special really are anymore real or special than alternatives.

You Might Also Like:

Some might want to call this a sort of natural kinds. Two things to this: 1) I don't want to commit to there being atomic properties like these (though I think it's quite plausible) and 2) sure, fine, if you want to call a belief in atomic properties a belief in natural kinds, be my guest—then I'm just against composite natural kinds.

I was about to write a comment until I saw footnote 1: yes, that is pretty much what I was going to say.

Lewis thoughts the properties fundamental physics was trying to discover were the maximally natural properties. He also thought properties constructed out of maximally natural properties via simpler chains of definition were *more* natural than properties constructed out of maximally natural properties via complex chains of definition. You reject that latter claim.

But it seems to me there's a big difference, and you'll want really different arguments, if you're accepting that there's some deep distinction between the fundamental properties (mass, charge, spin, maybe consciousness if you want to go that way) and everything else, versus a view on which there are no fundamental properties, and the various categories that can be used in modeling bits of the world, whether from particle physics or economics, are all metaphysically on a par (I think Nancy Cartwright has this view).

Yet another great post I find myself disagreeing with! I'm scared for the day you post something I'm forced to praise uncritically.

I take it that the sort of ostensive definition that is supposed to get the idea of natural kinds in our heads, is pointing at the sorts of categories used in scientific practices, noting their projectability, and conferring a special status on those 'sorts' of categories called 'natural kind-hood'. Consequently, the most important feature of natural kinds is their projectability. Now, you ask us to imagine a scenario where "Sold and gilver" are natural kinds, but presumably the natural kind realist is going to reject that such a scenario is possible. Ex hypothesi, the sorts of projections we are able to make about gold and silver don't work on sold and gilver, because sold and gilver are gerrymandered around temperature. So the success of projections like "X is gilver, and so X is pale in coloration" will be far less successful than "X is silver, and so X is pale in coloration." As a consequence, it doesn't seem like sold and gilver will meet the projectability bar the realist wants for their kinds. I also think this reply helps answer your question of how natural kinds matter. It seems to me like the idea behind natural kinds is that they are the most projectable categorizations, that is the sense in which they 'matter', they are deeply intertwined with our best scientific practices.

Now, some of what you say probably counts against natural kind views that require some sort of metaphysical goop that is supposed to be what the natural kind is (aristotelian essences, platonic forms, whatever) but as far as I can tell, in the literature there are realist views about natural kinds which deny those sorts of things (namely promiscuous realism, but also various microstructural views). I agree with you that, getting rid of that goop or reassigning it to another category (par impossible) doesn't seem like it would matter, but that criticism doesn't seem like it would carry over to microstructuralists who are focused on particular sorts of underlying physical mechanisms.