Self-Defeat Doesn't Matter

A theory can be true and self-defeating

If you’ve ever taken an epistemology class, you’ll have had the following experience: The teacher is discussing skepticism and its possible scopes. Here global skepticism—the view that you cannot rationally believe anything—is brought up as the widest form and promptly dismissed on grounds of being self-defeating. After all to believe that would be to admit that your belief is not rational, so you should give it up.

While this is probably a pedagogically wise decision, it also reflects a problematic attitude common to many philosophers—that showing something to be self-defeating is enough to dismiss it. Aside from global skepticism, you see this with various theistic arguments like the evolutionary argument against naturalism, presuppositional apologetics, and the moral knowledge argument; as well as sometimes against certain metaethical positions.

This attitude is misguided! Showing a position to be self-defeating doesn’t show that it’s wrong—in fact it doesn’t even point in that direction.

Or, there are obviously some cases where self-defeat is a problem. For example:

Nothing is true.

This proposition is self-defeating in the sense that if it’s true it’s not true—and so it cannot be true. We don’t want that, and a theory that’s self-defeating in this way is no good. We can call this hard self-defeat.1 But there is also soft self-defeat, like:

Nothing can be rationally believed.

This could be true! If it’s true then, well… you can read what it says. Sure, you couldn’t rationally believe it, but it could be true without anyone rationally believing it! So soft self-defeat will usually have something to do with our relation to a position, like belief, knowledge, obligation, etc.

My claim is then that there’s nothing problematic about soft self-defeat: Showing a theory to be softly self-defeating doesn’t show that it’s false. I’m here very inspired by

’s amazing piece Caring about truth in philosophy, which honestly really changed how I think about certain issues.Really, I shouldn’t need to say more here than what I’ve already said: Showing a theory to be softly self-defeating doesn’t show that it’s false. So pointing out that global skepticism cannot be rationally believed or known or whatever doesn’t move forward the dialectic. For that to be a strike against the view, it must be that there is some case of, say, knowledge. But if you’ve gotten to the point where you’re resorting to pointing out self-defeat then you’re at a point where it’s plausible that there is no knowledge. And in any case, showing that the position is self-defeating doesn’t show that there are any cases of knowledge—so the point is moot.

I can’t deny that there’s something unstable or uncomfortable about self-defeating positions. Because, well, you can’t accept/endorse/rationally believe/whatever them. They are a perpetual cycle of being pulled in and pushed out, over and over, as your mind goes through the circular process of accepting them and then realizing that it can’t. But this doesn’t mean that you can accept the non-skeptical position.

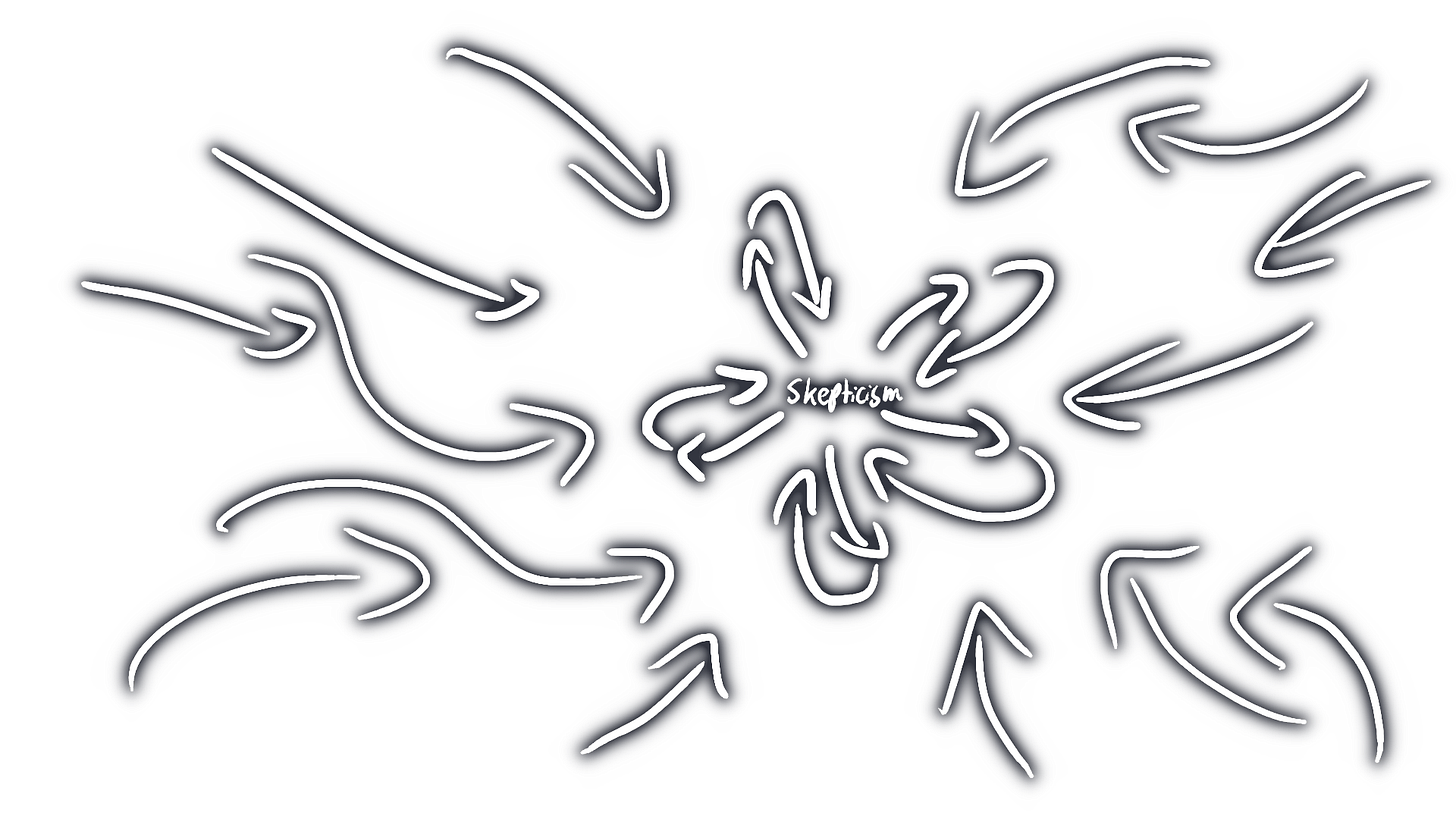

When thinking about this, I like to imagine myself swimming around in a body of water, with reasons being the currents driving me around. Swimming around in these waters, it might very well be that the currents of reasons turn out to be like this:

Sure, one can’t rest in the whirlpool of skepticism—but it’s still the most stable position, and if you try to swim out, you’re immediately sucked back in. This is what the epistemic landscape will look like if the arguments for global skepticism are good: If you stand in a spot where you take your cognitive faculties to be good/reliable/whatever, then you find that exercising them shows that they aren’t good—and you are swept with the current towards skepticism. That is, if the arguments for skepticism work, then every honest position is self-defeating. It’s just that skepticism is the position where the self-defeat turns back on itself.

There is, however, one sense in which self-defeat can reasonably guide you away from a position. The thing is, self-defeating positions are very unproductive. Once you’re caught in the whirlpool, then you can’t really do much—it’s not very constructive. Hence it can make sense to just decide not to care. Sure, we can’t bootstrap our way out of skepticism. But let’s just assume that we can trust induction, or that we may presumptively trust our appearances, or… And by doing this, we are able to actually live in the world.

For the record, I’m not sure how likely I think skepticism is. Probably not particularly. If you take nothing for granted, then you’ll never escape it; you’re stuck in a hole with no handles to climb out. But then it’s not obvious that you shouldn’t take anything for granted. Not taking anything for granted is still a position, and it doesn’t seem like the position that’ll give you the most true beliefs. What that position is, though, is the big question.

You Might Also Like:

For completeness we could also include theories where believing them entails their falsity, like “there are no beliefs,” or “I don’t exist.” But that’s not important for the main point here.

I was antecedently already sympathetic to the view that soft self defeat doesn’t mean much — I mean, it’s literally unconnected to truth. But, saying there’s “nothing wrong” with a view that is soft self-defeating can’t be right: showing that a view soft self-defeats puts a constraint on the view. Namely, it can never be the *winner* of an argument. You can never be *convinced* of it. Sure, that doesn’t mean it’s false — but we aren’t directly acquainted with The Truth. Our relation to The Truth is mediated by epistemology: we believe something when we have some reason to. That’s why some very handsome fellows have argued that the truth, per se, doesn’t even matter (https://substack.com/home/post/p-162561243?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web)

You talk towards the end about “what if the arguments for skepticism are good” but it seems to this is exactly the problem with self defeat, they can’t be! Suppose arguments for Skepticism were strong, then you would have good reason to be a skeptic. But if the self defeat problem rears its ugly head, you can basically modus tollens your way backwards to the conclusion that all the arguments for skepticism are bunk. So, then, suppose you have any reason at all to think skepticism is false, even if it is incredibly weak. From the self defeat claim the skeptic is forced into, you can basically infer the falsity of skepticism because all of the arguments have implicit in their conclusion that they suck! Now, of course, skepticism still might be true. But this is definitely dialectical progress (at least it seems to me)