For some reason, there are many people who don’t believe in evolution. I find this completely baffling! Not only do almost all experts agree that it’s true, which gives you strong reason to accept their word if you’re not an expert, but it just seems blindingly obvious that it would happen. In fact, I’ll go out on a limb and say that if you pointed it out to people in ancient times, or even hunter-gatherers—no “trust me bro, DNA is real” or anything—the at-least-somewhat-bright among them would have believed it. If you were unaware, I’m not actually a biologist (I’m sorry to break your bubble), which may make you suspect that I am not the highest authority on this subject (up for debate)—but I’m still the writer of the (stance independently) best blog on the internet, so any errors in what I say here have been put there by the devil himself. And in any case, I’ll try my best!

The reason that evolution is so obvious is that you basically only need three things to get it off the ground in a reproducing population:

Selective pressure: certain traits correlate with being more likely to have offspring (that survive to reproduce).

Heritability: offspring are more likely to have a given trait if the parent(s) had that trait.

Variation: traits are varied to some degree through reproduction.

In fact, it seems like you don’t even have to test whether evolution occurs when these are in place—you can just see that it will. Imagine this scenario (easy if you try): We are living in a world where philosophers are total studs (i.e. the actual world), meaning there’s a direct positive correlation between amounts of philosophy papers read and probability of procreation per year. Furthermore, some evil philosophy professors have gone rogue, and started quizzing people on philosophy questions, killing anyone who gets them wrong (e.g. average utilitatians). Lastly, the children of those who read many philosophy papers are themselves more likely to read many philosophy papers (with some random variation). Suppose that you start out with a completely arbitrary distribution of philosophy-interest throughout a population. Chads like those who read this blog will both be more likely to survive and more likely to get laid, meaning they will be more likely to have children (selective pressure). Furthermore, since the children of such masters of sex-appeal are themselves more likely to have an interest in philosophy, they too will have more children, meaning that the average level of philosophy-interest will increase for each generation (heritability).

In fact, even if there was initially no interest in philosophy, if we allow for random mutation, an interest in philosophy will eventually emerge through brute luck (variation). When this happens, the lucky bearer of this trait will immediately become irresistible to anyone who hears their sultry voice go into the sexy details of conceptual engineering vs. conceptual analysis, or theories for decision making under normative uncertainty—I am having a hard time containing myself, just thinking about it! 🥵 This will invariably lead to them having loads of children (since antinatalism is obviously false, as any philosopher worth their seductive aura will know), meaning the ball is now rolling, and philosophy interest will become a widespread trait.

More abstractly, we can imagine that we have a population in a situation where there is a selective pressure in favor of trait T (and suppose for simplicity that this is the only pressure). For any arbitrary distribution of these traits, the probability that a given individual will reproduce is greater if the individual exhibits T to a greater degree. This means that for each generation, there will be proportionally more offspring from parents with higher degrees of T than with lower, than those parents represent in the previous generation (on average). Since offspring of parents with high degrees of T are more likely to exhibit higher degrees of T themselves, this means that for each generation, the proportion of individuals with high degrees of T will increase (again, on average). This, I take it, is just what evolution is: some trait becomes more prevalent in a population due to selective pressures. Now, we still need to address the edge-case where T is not represented in the population to begin with. Here variation comes into play: if T is reachable through variation, then after sufficiently many generations, T will occur to at least some degree in at least one individual. We can then reason as if that generation were the first generation, and we are off the ground again. Without variation, it also looks like the degree of T in any individual could never exceed the largest degree found in any individual in the initial generation, meaning variation also accounts for increases in maximum values of T (and likewise for minimum values). This is of course only one trait, with a fixed selective pressure, meaning it is very simplified, but it should make it clear how we can almost “derive” evolution from these three conditions.

As you may remember from around 750 words ago, I made the somewhat bold claim that you should be able to make hunter-gatherers see that evolution occurs pretty straightforwardly. I think that you could, with time, pretty easily convince a rational human that these three conditions make evolution highly probable to occur. So the question now becomes whether we can observe these three conditions being satisfied in everyday life. Selective pressure is very obvious: some people reproduce more than others, and some people survive longer than others. Furthermore, there are obvious traits that make these outcomes more likely—being intelligent and strong (generally) makes you more likely to survive (at the very least in prehistoric times), and being an analytic philosopher is way sexier than being a virgin STEMlord, meaning the former get laid more often (trust me).

Heritability should also be pretty obvious to everyone: people with brown hair are more likely to have children with brown hair, likewise with eye-color, skin-color, etc. It’s of course also important that the heritable traits are ones relevant for fitness. This is a little more difficult. For a start, we can begin by noticing that any trait could in principle be fitness-conducive. For example, in a world where God hated red-haired people and smote1 them at random, having red hair would decrease fitness. Likewise, if everyone found red hair to be the hottest thing since [some very warm object], having red hair would increase fitness (in fact in today’s society, being slim and tall probably gives some increase in fitness). Furthermore, some traits that are heritable would obviously have an effect on fitness in hunter-gatherer time. For example, being tall would maybe make you better able to reach certain food sources, or being intelligent would make you better at solving problems necessary for survival.2

If there were no variation, we should expect siblings to be perfectly identical, since they were created by the same set of parents. Furthermore, many traits would eventually converge. For example, given heritability and no variation, a child of a tall mother and a short father would presumably have a height somewhere in-between. Thus with time, everyone would converge to being the same height (and likewise with other traits that are inherited in this way). But we observe many differences between people, and they don’t seem to be getting smaller, so it looks like variation is also plausibly discoverable through everyday experience.

I think it would then be pretty obvious that at least certain traits evolve. It is a little harder to see how wildly different species can come about, but if you convince yourself that differences between species are a matter of degree rather than kind—after all, you can imagine me continually transforming into a pike—then it’s not so surprising that very different creatures could arise after enough time. Additionally, if you convinced the people to dissect some vertebrates, they would discover the same body plan as humans, and especially with mammals it would be very easy to imagine a gradual change from one to another (or really from a common ancestor to each).

I must admit that these arguments from everyday experience are pretty weak—as is to be expected, since everyday experience doesn’t lend itself very well to these sorts of inferences—but I think that they could plausibly convince at least some rational hunter gatherers, if they took the time to think about it. With more modern discoveries, like DNA making it clear how this process of inheritance with variation works, and fossil records cohering very well with what we would expect if species had arisen from continuous evolution, I don’t think there is really much excuse not to believe in biological evolution.

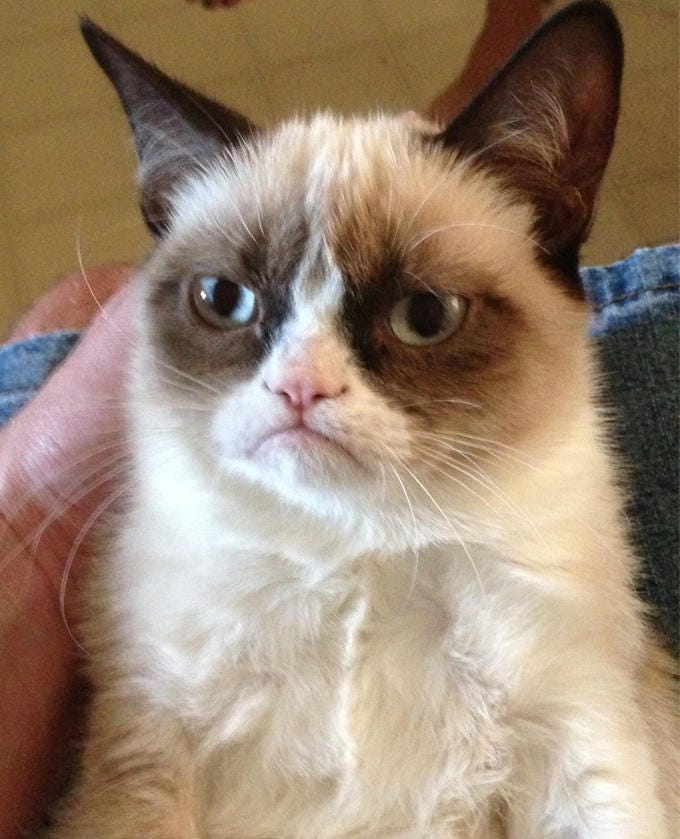

The three conditions obviously don’t just apply to biology—evolution can, and often does, occur in other contexts, especially that of ideas. Memes, in the original sense coined by Richard Dawkins, are simply units of cultural information that evolve. As an example, Memes in the colloquial sense are—you guessed it—memes (here, have a gold star)! For instance, when a hip internet-surfer in 2012 would see this picture:

They would very likely to share it (reproduction)—OMG look at that wittle cat, she looks so angry, but she’s also a little cat! That’s so funny AHAHAHAHAH! This is because it (the image, that is) has a certain traits that are conducive to survival and reproduction, such as being the angriest littlest cat you have ever seen and being so damn hilarious because she looks like a little old man who is angry but also a cat! Here, then, we have selective pressure. Furthermore, when shared, there is in principle perfect heritability of all traits of the image (since nothing is usually changed), BUT some people may be inspired to make modifications to the image such as:

which amounts to variation. Some of these result in new traits that have a higher fitness (she’s so grumpy she doesn’t even like fun, looooool). And so we have all the components sufficient for evolution: memes have traits that make them more or less likely to replicate, which the replicas inherit with some chance of variation. Beyond the funniest images of cats you’ll ever see in your whole life (ROFL), this also applies to stuff like styles of music, political and philosophical ideas, ways of building houses, etc.—the world is your oyster, evolution!

But when it’s so obvious that evolution will occur in all kinds of places, including in biological creatures, it makes you wonder why it took so long to figure out—were people just stupid? Probably not. Rather, something can be very obvious once you see it, but still incredibly hard to be the first to discover—once you understand Cantor's diagonal argument, it’s very obvious that it works, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t very hard to be the first to discover. Likewise, evolution is just not obvious until you pay attention to it.

I suspect that most of you are not very surprised by what I have been arguing in this post—you may even find it trivial—but that just makes me all the more dumbfounded that there are actually people who still don't believe evolution, even after having it told to them, as it seems something approaching a conceptual truth that it would happen in populations like ours.

I definitely didn’t look up the past tense of “smite” for this.

It may not be as obvious that intelligence is inherited, as it also has a lot to do with upbringing (as is of course the case for many other traits, including height), but assuming that several families would share the task of raising children, at least some would probably notice that the children of smarter parents were themselves smarter. This would indicate that it is a biologically inherited trait. Furthermore, even if traits like these could not easily be observed to be biologically heritable, we would at the very least have had strong evidence for cultural evolution, with regards to the factors responsible for these traits.

I agree evolution is totes fr, but I’m not sure a caveman could’ve had his worries about—say—irreducible complexity resolved a priori

I’m religious, and most religious people I know have no issue believing in evolution meaning variation/selection pressure/heritability. But them, including me, would take issue with thinking the existence of evolution proves that there isn’t a God who had a hand in creation. Often when people say they don’t believe in evolution, that’s what they really mean.