Thoughts Without Intuitions Are Empty

On Henri Bergson and what is real

How do we know what is real? What in the world does it even mean for something to be real? Yeah, yeah, real original of me, asking these innovative questions. Really breaking new territory here!

But really, it’s not very easy to say. It does, however, seem to me that certain attempts to answer this question have been, as the kids say, lost in the analytical sauce—to the point where they no longer seem to be talking about the same thing that we started out interested in. Here I’m particularly thinking of the views of J.M.E. McTaggart, Rudolph Carnap, and Nelson Goodman (who are all, by an incredible stroke of coincidence on my metaphysics curriculum).

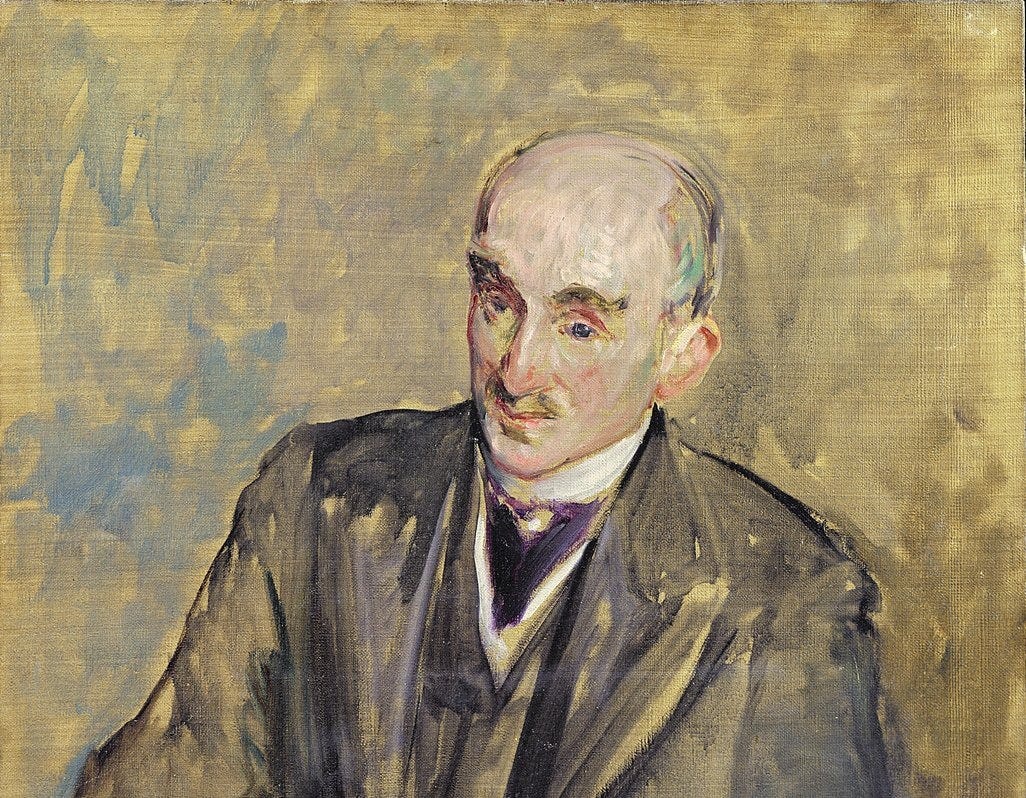

And to bring us back to our senses, we look at Henri Bergson—him to whom we turn when all hope is lost. I think his methodology based on intuition provides a good remedy to the above views. To be clear he has an idiosyncratic use of “intuition,” so I’m not here taking a stand in the great intuition-wars ravaging Substack. But you’ll learn more about that when we get there.

McTaggart: Time Isn’t Real

According to McTaggart time is not real. I know, I know—very normal conclusion to reach! He distinguished two ways of seeing time: As comprising an A-series and as comprising a B-series. In an A-series, temporal positions are ordered by relations of pastness, presentness, and futurity; whereas in a B-series, temporal positions are only ordered by relations of earlier-than, later-than, and simultaneous-with.

The argument—in rough outline—goes as follows:

If time is real, it is either an A-series or a B-series.

It is essential for time that there is change.

If time is a B-series, then there is no change.

So, time is not a B-series (2, 3)

If time is an A-series, then events must have inconsistent properties (pastness, presentness, and futurity)

Nothing can have inconsistent properties.

So, time is not an A-series (5, 6)

Therefore time is not real (1, 4, 7)

For our purposes, the substance of the argument isn’t of particular interest. What is of interest is the batshit conclusion.

In denying the reality of time, McTaggart doesn’t wholly abandon the idea that the world consists of ordered events. Rather, he claims that reality is ordered according to a C-series. This bears a remarkable semblance to the B-series, except that the relations between events are not temporal, but merely some other kind of non-temporal ordering relations. Cool, cool, cool.

We are left with a puzzle, however. If McTaggart’s conclusion is right, we are not creatures that endure through time, but simply a succession of time-slices or events that at best perdure. The trouble is that we very much appear to endure through time—or at the very least, time seems to pass in a way which the C-series does not permit. To accommodate this, McTaggart claims that time is illusory in a certain sense. There is nothing illusory about the appearance of ordered events. But our interpretation or experience of these events as being temporally ordered, rather than merely ordered simpliciter, is illusory.

Observing McTaggart’s handling of this problem tells us something interesting about his methodology. It tells us that McTaggart sees reality as fundamentally conceptualizable, and when our immediate experience conflicts with what our conceptual thinking tells us, it is the experience that has to go—or be reinterpreted. Thus for McTaggart our primary way of coming to know reality is through conceptual reasoning rather than immediate experience. At this point we should start to hear the soft tinkle of alarm bells in the background.

Carnap: Everything Is, like, Relative, Dude

Whereas for McTaggart we had to tease out his fundamental assumptions through interpretation, the process is somewhat more straightforward once we turn to Carnap.

For Carnap it does not make sense to speak unqualifiedly of “reality.” Rather we have to distinguish two ways of asking “what is real”: We can ask it either as an internal or as an external question, relative to some linguistic framework.

Answering an internal question is, in principle, quite straightforward. A linguistic framework will have certain rules for evaluating propositions, either through empirical investigation or deductive rules. An entity exists within a framework if the framework allows true statements that assert its existence. Hence the number 2 trivially exists according to the linguistic framework of Peano arithmetic because “2 is the successor of 1” is true according to that framework; and similarly protons exist according to the physics-framework, because “a hydrogen atom contains 1 proton” is true according to this framework.

External questions, on the other hand, ask not whether some entity exists according to a framework, but whether it really exists—independently of any framework. According to Carnap, such questions are meaningless as theoretical questions, since for a question to be meaningful it must be formulated within a linguistic framework that provides rules for how to answer it. External questions, by definition, are not so formulated, and thus lack cognitive content. Still, Carnap allows that external questions may have a practical sense: we can meaningfully ask whether to adopt or reject a certain framework as a matter of convenience or usefulness.

Hence, for Carnap, what we can meaningfully call “reality” is always framework-relative. The supposed “real reality” beyond all frameworks is not a second kind of reality but an empty notion generated by misuse of language. Our relation to reality is therefore twofold: first, we determine what is real within a given framework; second, we make pragmatic choices among frameworks themselves. There are no “true” frameworks, for that would require answers to external theoretical questions. Frameworks are instead adopted on pragmatic grounds—by decisions about what systems of language and rules best serve our explanatory purposes.

Carnap, like McTaggart, clashes with common experience in a troubling way. His linguistic framing of ontology makes existence claims both too easy and uninformative. In his system, whether electrons exist is simply a matter of whether our physical theories quantify over them—but this misses the point. The question that interests us is not whether electrons are mentioned in our theories, but whether they correspond to anything “out there.”

Not just this. For Carnap, questions gain meaning only by fitting into a linguistic framework, not from pre-linguistic encounters with the world. Even a report like “I see something red” is judged true or false according to framework rules. But this reverses the proper order: we develop frameworks to capture and convey our immediate experience, not to subordinate experience to language. Treating the world as derivative of frameworks seems to deny the very encounter with reality that frameworks are meant to make intelligible.

Or diagnosed a little more carefully: Carnap seems to think that linguistic frameworks are prior to reality, when really it should be the other way around. We don’t decide what exists by choosing a framework—we choose frameworks to describe what exists! When this gets flipped around, we lose contact with what we were trying to talk about in the first place.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wonder and Aporia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.