The Divine Repugnant Conclusion: A Theodicy

The problem of evil is one of the oldest and most persistent problems to haunt theism. But there could still be hope, and the savior is not who you might expect: The philosopher Derek Parfit.

1. The Problem of Evil

Probably the most common objection to theism is the problem of evil. In its most basic form, it is something like: “If God, why evil?” This is probably the first thing someone will come up with as an objection when considering theism, and it remains a big point of discussion in contemporary philosophy of religion. A more rigorous formulation of the problem might sound something like this:

Evil exists

If God an omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent God exists, then evil would not exist

If God is omnipotent, then if he wanted to stop evil that he knew about, he would do it.

If God is omniscient, he would know about evil

If God is omnibenevolent, he would want to stop evil

If God stopped evil, then evil would not exist.

Therefore an omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent God does not exist.

Here evil is just defined as anything bad (or perhaps any gratuitous bad). This argument is obviously valid. The premises all seem true too, so how does the theist avoid this argument? Most deny premise 2, and specifically premise 2c. Why might we doubt this premise? This is where theodicies come in. These are stories that explain how evil is consistent with the nature of God. I will try to give one such story here, which builds upon some of Derek Parfit’s work in population ethics.

2. The Non-Identity Problem and the Repugnant Conclusion

In the fourth chapter of Derek Parfit’s Reasons and Persons, Parfit considers how we should make ethical judgements about future generations (specifically he considers what is the right principle of beneficence. If you are a deontologist this is still relevant. You will plausibly still have to accept a principle of beneficence, although rights will act as side-constraints on beneficence). Here he raises two problems, which have since become quite famous in philosophy (which means not very famous generally). I will here quickly lay out the problems:

2.1. The Non-Identity problem

The non-identity problem is basically the question “how should we treat decisions between future outcomes A and B, when none of the people who will exist in A will exist in B, and vice versa?” This is illustrated with the example of a risky policy:

A current government is deciding between two policies A (for example building a nuclear reactor) and B (not building it). If they choose A, this will produce a small increase in utils (or whatever we value in our principle of beneficence (add this in your head whenever I say “utils”, as I don’t want to add this clarification every time)) for all the people living now, but within 1000 years it will almost certainly cause a big catastrophe. This catastrophe would drastically decrease the QOL (quality of life) of all future people, however their lives would still be well worth living (for example we might imagine that they live regular lives until the age of 40, where they quickly die of cancer). If they choose B, the welfare of currently living people would be slightly lower, but no catastrophe would occur, and the lives of all future people would be drastically better. We will also postulate that none of the future people in A will be the same as the future people in B (and vice versa). The government then argues as follows:

”If we choose A, no people will be harmed, since the people that will exist would not have existed, if we had not chosen A. Thus it cannot be wrong to choose A, since no people are harmed, and some might even be benefitted (if we think that bringing into existence can benefit).”

We are of course supposed to think that this argument is terrible. But why is it? It seems that the best answer is that a principle of beneficence should not be person-relative. In other words, an act can still be wrong, even if no one is harmed by the act. This principle is very plausible when considering cases where the same number of people would exist in each outcome. But what about different-number cases?

2.2. The Repugnant Conclusion

In different-number cases, we might consider two possible principles:

The highest sum principle: When choosing between two outcomes, we should prefer the outcome with the highest sum of utils.

The highest average principle: When choosing between two outcomes, we should prefer the outcome with the highest average of utils per person.

These are both equivalent in same-number cases, but they will often differ in different-number cases. Which should we prefer? Let us consider an example:

The two hells:

Hell A: In hell A 100 people endure 50 years of extreme suffering. They would all very much prefer to be killed than to endure another moment in this hell.

Hell B: In hell B 1,000,000,000 people endure the same degree of suffering, but one person only endures it for 50 years minus 1 second.

Which should we prefer? Obviously Hell A. However the average principle says we should prefer Hell B, and thus these examples seem to provide a reductio against the average principle. What about the highest sum principle? This is where Parfit introduces the famous Repugnant conclusion. Consider the following possible states of affairs:

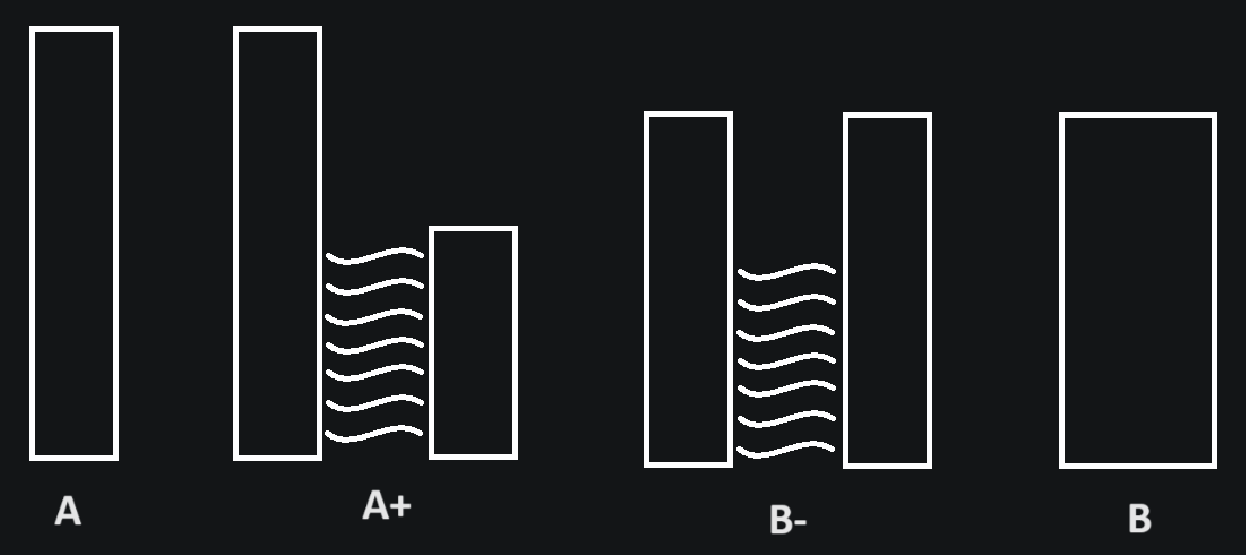

Here the height of a block represents the amount of utils each person has, and the width represents the amount of people. We will here stipulate that no people are shared between different states of affairs (now the conclusion about the non-identity problem becomes quite important: We can still prefer one outcome over another, even if no person is made better off by either outcome). In A, 1 billion people are very well off. In A+ There are 1 billion people who are very well off, and an additional 1 billion people who are quite well off (they still have lives well worth living). The waves represent there being no causal connection between the two groups, blocking any plausible consideration of equality. A+ is obviously better than or equal to A, since there is nothing worse about it, and there are some additional people who are also well off. In B- both groups have an equal amount of utils. No-one is here made worse off, since A+ and B- share none of the same people. Additionally the sum and average are here higher than in A+. Thus B- is obviously better than or equal to A+. In B there is no barrier between groups. It is not at all clear why this should make a moral difference. If we accept all this (and assuming transitivity of value), then we reach the conclusion that B is better than or equal to A. Now consider the following states of affairs:

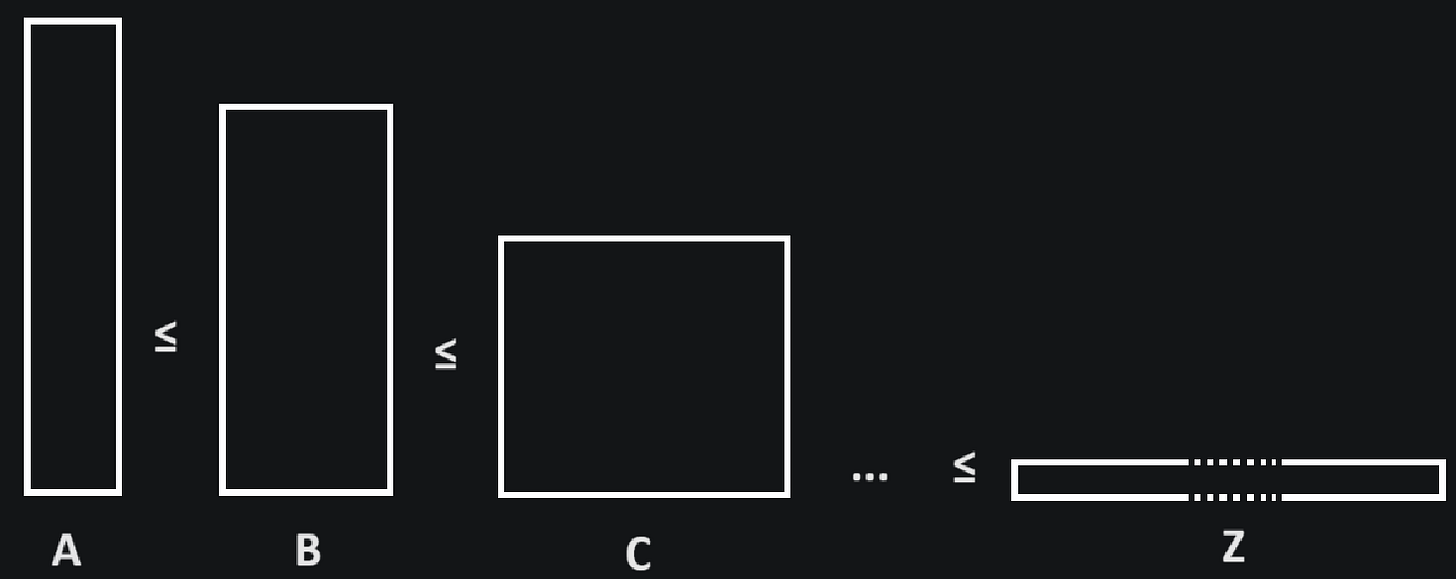

That B is better than or equal to A was argued above. The step from B to C follows the exact same argument. This inference could be repeated until we reach Z; a world where a very large amount of people live lives barely worth living. As argued above, this world is better than or as good as A. Thus we have reached the repugnant conclusion: For any possible world, there is a world that is at least as good, containing a large amount of people with lives barely worth living.

2.3. How Implausible is this Conclusion?

How should we respond to this? If we accept the average principle, then we avoid the repugnant conclusion (this blocks the inference that A+ is as good as or better than A). This principle, however, also entails that Hell B is better than Hell A, which is much more absurd than the repugnant conclusion. There are several other possible principles to consider, but it is far beyond the scope of this post to discuss these. I will just disclose that I think we should accept the highest sum principle (which, again, is not incompatible with deontology), and accept the Repugnant Conclusion.

To make this conclusion less repugnant, let us consider what it means to have a life barely worth living. In your head you might think of people living on the brink of starvation, barely scraping by. I do not think this is what it means - such people might plausibly have lives that are not worth living, when looked at in terms of beneficence at least. I think a better way to imagine it is someone who has a completely bland life, feeling no pain and no pleasure, except on their 23rd birthday, where they receive a compliment. This is not a very good life, but it is also obviously not a bad life. We might reject the value of such lives due to aesthetic considerations, but it is very hard to see how such lives could be morally bad.

I think our intuitions are also skewed by the practicality of lives barely worth living. Consider 10 very good lives or 100 lives barely worth living. We can assume that there is a higher sum of utils in the 10 former lives, than in the latter 100. Still, it would very plausibly require many more resources to sustain the 100, since they would all require food and shelter in order to have lives that are not bad. This means that we very rarely stand in decisions such as the choice between A and Z - We could almost always produce more utility by spending the same amount of resources on fewer people.

Thus, I think that we should accept the repugnant conclusion, all things considered.

3. The Divine Repugnant Conclusion

With all that groundwork laid, let us now return to the problem of evil, and specifically to premise 2c from the argument above:

”If God is omnibenevolent, he would want to stop evil”

Why should we reject this premise? Consider world A:

God creates Adam and Eve, who live 80 years experiencing no pains or evils, and experiencing great finite goods.

It is very plausible that it would be permissible for God to create such a state of affairs - if we do not think it is permissible to create this state of affairs, it is hard to see how any state of affairs could be permissible for God to create. Now consider instead world A+:

God instead created Adam, Eve and Steve. Adam and Eve live corresponding lives to the Adam and Eve of world A. Steve lives 80 years on a separate planet, where he lives as good a life as Adam and Eve, except that he stubs his toe 4 times throughout his life. Steve still is still very much glad to be alive, and his life is very worth living. If you ask him at his deathbed whether he would rather not have been created, he answers “of course not!”

Would it be permissible for God to create such a world? This world has strictly more utils than A, and it is hard to see how the mere addition of another life worth living could make this world worse. Thus it looks very plausible that God would be allowed to create this world. Lastly, consider world B:

God creates Adam, Eve and Steve. They all live lives corresponding to the lives of Adam and Eve in world A, except that they each stub their toe once.

This world is obviously at least as good as world A+, since there is less pain all in all, and the same amount of pleasure. Additionally, the pain is distributed more equally.

The keen reader will have noticed a certain similarity between these cases, and the argument for the repugnant conclusion above. This is no mistake, and the conclusion will here be the same: If we accept the reasoning above, we should accept the Divine Repugnant Conclusion: For any world that it is permissible for God to create, there is another possible world containing many lives that are barely worth living, which it is permissible for God to create. Furthermore the actual word seems to lie somewhere between A, and a world containing only lives barely worth living; it seems most people have lives that are quite worth living.

Is this argument any good? I can anticipate a few objections.

3.1 Objection: God could always have created a better world.

This objection targets the step of the argument that claims that A+ is at least as good as A (which I also think is the least plausible step). We might say something like this:

“When we were considering world A and A+ in the repugnant conclusion, we were only given a choice between two possible states of affairs. But God could bring about any possible states of affairs. Thus the choice is not between A and A+, but between A, A+ and C, where C is equivalent to A+, except Steve never stubs his toe. In this choice, it would not be permissible to bring about A+.”

I think this objection is quite good. It points out that the choice is not as much like the choice between A and A+, but rather like the risky policy example, where God can either bring about a Steve who stubs his toe, or Schmeve, who does not stub his toe. Here the choice is obvious: He should choose Schmeve. I think there is quite a bit of plausibility to this objection, although I can think of a possible answer. God is not only choosing between, A, A+, B and Schmeve. Rather he is choosing between ALL states of affairs he could bring about. So if he chose to bring about Schmeve rather than Steve, we might plausibly ask why he did not let Schmeve live another year of pleasure, or why he did not also bring about Schmadam, who lives a life equivalent to Adam and Eve. More generally, for any state of affairs God brings about, he could always bring about one that was slightly better. With what principle should God then choose? One principle might be that God may not choose any state of affairs. I find this quite implausible, however. Consider:

John Pollock’s EverBetter Wine: Suppose John is a wine taster, who has acquired a bottle of EverBetter™ Wine. Unlike normal wine, this wine will always become better with age. Suppose that after 10 years, John decides to drink the wine. Is this irrational? John could of course have waited another moment, or another year, or another 10 years, and the wine would have been even better. In fact for any moment there will always be a later moment in which would be better for John to drink the wine (assume John is immortal). So John should never drink the wine? One day John wants to share a glass of the wine with his friend Jill. But if he chooses to share the wine today, he will be acting immorally, since John could have brought Jill more pleasure by waiting a day before sharing the wine. So John should never share the wine?

The answer to both of these questions is obviously no! Of course it is permissible for John to choose a moment to drink or share the wine. Furthermore, returning to the case at hand, if you ask Steve, he would rather have existed than not. It is of course also true that he would rather not have stubbed his toe. But for any state of affairs there is always one Steve would prefer to have been put in. This does not, however, mean that Steve would prefer not to have existed, just because there is no best possible life for Steve.

Rather than it being impermissible for God to choose any state of affairs to bring about, I think we should rather conclude that it would be permissible for God to bring about any state of affairs that is on the whole good, even if it is not the best possible state of affairs.

3.2 Objection: God may not bring about any (excessive) evil.

Another thing we might think is the following:

“The problem is not that God brings about a state of affairs that is not the best, but that he brings about a state of affairs that is positively bad. Sure, he might be permitted to bring about a state of affairs that is not the best, but if that state of affairs includes some gratuitous evil, then that is a different story; you may not give a person $100, and then kick them in the groin, even if the sum of those actions is positive.”

Again, I think this objection is quite good. It seems very plausible that God ought not to allow some gratuitous evil, even if the world in which it occurs is good. In fact, when faced with the problem of gratuitous evil, theists will usually rather deny that there is gratuitous evil, than that God would allow such evil. I do think, however, that we might give an argument against this principle. Consider the following two states of affairs:

A: Steve lives a life of great finite goods and no pains for 50 years, and then dies.

B: Steve lives a life of great finite goods and no pains for 50 years. On his 51th birthday he stubs his toe, and then lives another 30 years of great finite goods and no pains before he dies.

If there was a person behind a veil of ignorance, who knew that they would be either Steve A or Steve B, which should they hope to be? I hope we can all agree that they should hope to be Steve B (unless we think that suffering has lexical priority over pleasure, which I think is extremely implausible). This suggests that B is better than A: There is only one moral subject in each case, and if given the choice we should choose B. Would It be permissible for God to bring about A? If it is permissible for God to bring about anything, then surely he would be allowed to bring about a life of great pleasure and no suffering. Let me now introduce a principle:

Transitivity of Permissibility (ToP): If there is any state of affairs P that it is permissible for God to bring about, then it is also permissible for God to bring about any states of affairs that are as good as or better than P.

If we reject the antecedent of this implication, then there is no way we ever accept theism, since we are currently living in a state of affairs. Our existing would then be conclusive proof against theism, and thus it would be strange that we would have made it this far into the dialectic. What about the consequent? Well, intuitively, if God was choosing between 3 equally good states of affairs to bring about, we wouldn’t think that there would be any principled way to favor one over the others. This seems to show that if it is permissible to bring one about one of them, it would be permissible to bring ANY of them about. Now imagine that there was a fourth option that was even better. Here we would think that that one was certainly permissible, if the worse ones were permissible. This is more of an intuition pump for the ToP than a principled argument, but I do think that it is very plausible.

If we accept the above, then it looks as if we should accept the following argument:

Consider the following 4 states of affairs:

A: God creates Adam and Eve, who live 80 years experiencing no pains or evils, and experiencing great finite goods.

A+: God creates Adam and Eve, who live 80 years experiencing no pains or evils, and experiencing great finite goods. Additionally, on a separate planet he creates Steve B, who lives 50 years of bliss.

A++: God creates Adam and Eve, who live 80 years experiencing no pains or evils, and experiencing great finite goods. Additionally, on a separate planet he creates Steve A, who lives 80 years of bliss, except that he stubs his toe 4 times.

B: God creates Adam, Eve and Steve. They all live lives corresponding to the lives of Adam and Eve in world A, except that they each stub their toe once.

It seems we should accept that A is permissible, since it contains only lives of bliss and no suffering. Additionally the mere addition of another separate life of bliss and no suffering should not make it impermissible for God to bring about A+. Now consider A++. As argued above, when considering only the lives of Steve A and Steve B, the world with Steve B was better. This case is exactly similar, except that Steve A++ stubs his toe 3 more times (a minor difference), and that there are two perfectly happy people in no vicinity of Steve. Here again, it looks as if A++ is as good as or better than A+. Finally distributing the toe-stubbings more equally, and reducing their number by 1 would not make B worse than A++. Applying the ToP here, we must conclude that B is permissible. Repeating this argument would allow us to get any distribution of lives worth living, including the actual distribution. Thus it is permissible for God to create the actual world.

I must admit that I am still left with a bad taste in my mouth. There is just something so convincing about the idea that God would not allow gratuitous suffering: How could it be okay for God watch a child get raped or a city blown up for no reason, just because some abstract inference-rule says that it is okay all things considered? Why would God ever choose a world containing this much suffering, just because it is permissible? The best way I can describe it is that the argument is like a duck-rabbit illusion in my mind. One second i consider it, and I see how it is permissible for God to allow any distribution of lives worth living, and the next I see how it is impermissible for God to allow gratuitous suffering. You might feel the same (or you might think that my argument is terrible, and that God obviously doesn’t exist). This is also how the question of theism and atheism seems to me generally; one moment I can’t see how there couldn’t be a God responsible for the world and all its beauty, and the next it is odd to me that I could ever think such a thing, considering how devoid the universe seems of anyone in charge.

Enough of that, there is still one more objection I want to consider.

3.3. Objection: Lives not worth living

There is still one obvious hole in my argument: It has all been an argument for the conclusion that God could allow any distribution of lives worth living. But it is far from obvious that all lives are worth living. Consider the infant who chokes and dies shortly after death, or the the deer kid that is born with a deformed leg and is quickly eaten by predators. These all seem to be lives that are clearly not worth living. So this defeats my argument.

Except that I want to argue that there are no lives not worth living. I do not want to deny that some earthly lives are not worth living, but rather I want to introduce the (familiar) auxiliary hypothesis of an afterlife. As Richard Swinburne rightly points out, the addition of this hypothesis obviously lowers the probability of theism somewhat (although it is a theoretical cost that most theists are very happy to accept), but it does help us with the problem at hand.

If we add this hypothesis, then it turns out that all lives can be worth living, despite appearances. We do not need an infinite afterlife to achieve this, although many would not be against the idea of that. This of course presupposes a universalist eschatology, or something close enough. Luckily this is also obviously the right view (sorry ECT-believers).

3.4. Can bringing into existence violate someone’s rights?

Finally, all of this discussion has been in terms of beneficence, but as I said earlier, a principle of beneficence can still be consistent with having rights (or other values) as side-constraints. This leaves open the question of whether God could violate someone’s rights by bringing them into existence. Sadly this post is already very long, so I will not be able to discuss this in very great detail (I swear that it has nothing to do with this also being a very difficult topic, that I am not myself sure about). I will, however, just quickly mention a possible way out, if it turns out that God could violate our rights by bringing us into existence.

The idea hear is that of waiving rights. It is commonly accepted that if we do have rights, then we also have the ability to waive these, if we so choose. For example, you might have a right to bodily autonomy, but if you choose to participate in some BDSM, you thereby temporarily waive this right. Or you might have a property right to own the things you produce, but by signing a contract and working in a factory you waive this right with regards to the things produced when you are at work. This leaves open a possibility. Perhaps God knows the counterfactuals of creaturely freedom, and knows that if you were asked, you would want to waive your right and be brought into existence. Even if he does not know these counterfactuals, he could perhaps have asked you, before you were born, and you then agreed. To some people this would seem very implausible, as they find their lived not worth living, but perhaps if they became convinced of there being an afterlife, they would still want to be born, all things considered.

Then there are of course also anti-natalists, who think that being brought into existence is always bad. If you are an anti-natalist, then you probably think that all my arguments so far are terrible, so I am surprised you are still here. Anyways, this still leaves the question for the rest of us: How could these people have consented? Well, we can assume that the consent in question is given in ideal circumstances, with you having all the relevant information, and being perfectly rational (or as rational as possible). In these circumstances they would of course no longer be anti-natalists (just kidding… a little).

This solution is far from elegant, and if given the choice of this solution and any other, we should usually choose the other. But it does show that it would at least not be impossible for God to bring us about, even if bringing about can violate rights. And that is all that is needed.

4. Conclusions

Phew! That was a long post. Where does this leave us? If we accept all the arguments above, then that seems to lighten the weight of the problem of evil a lot, since it would mean that it would be permissible for God (when considering only beneficence) to create any world with people all of whose lives are worth living. This could also be paired with other theodicies. I do not, however, expect that many people find these arguments perfectly convincing, as there are many points where one might object, especially on the question of gratuitous evil. I am myself not quite sure how confident I am in this argument, although I do think it is a fun one, and I think there might be at least some potential here.