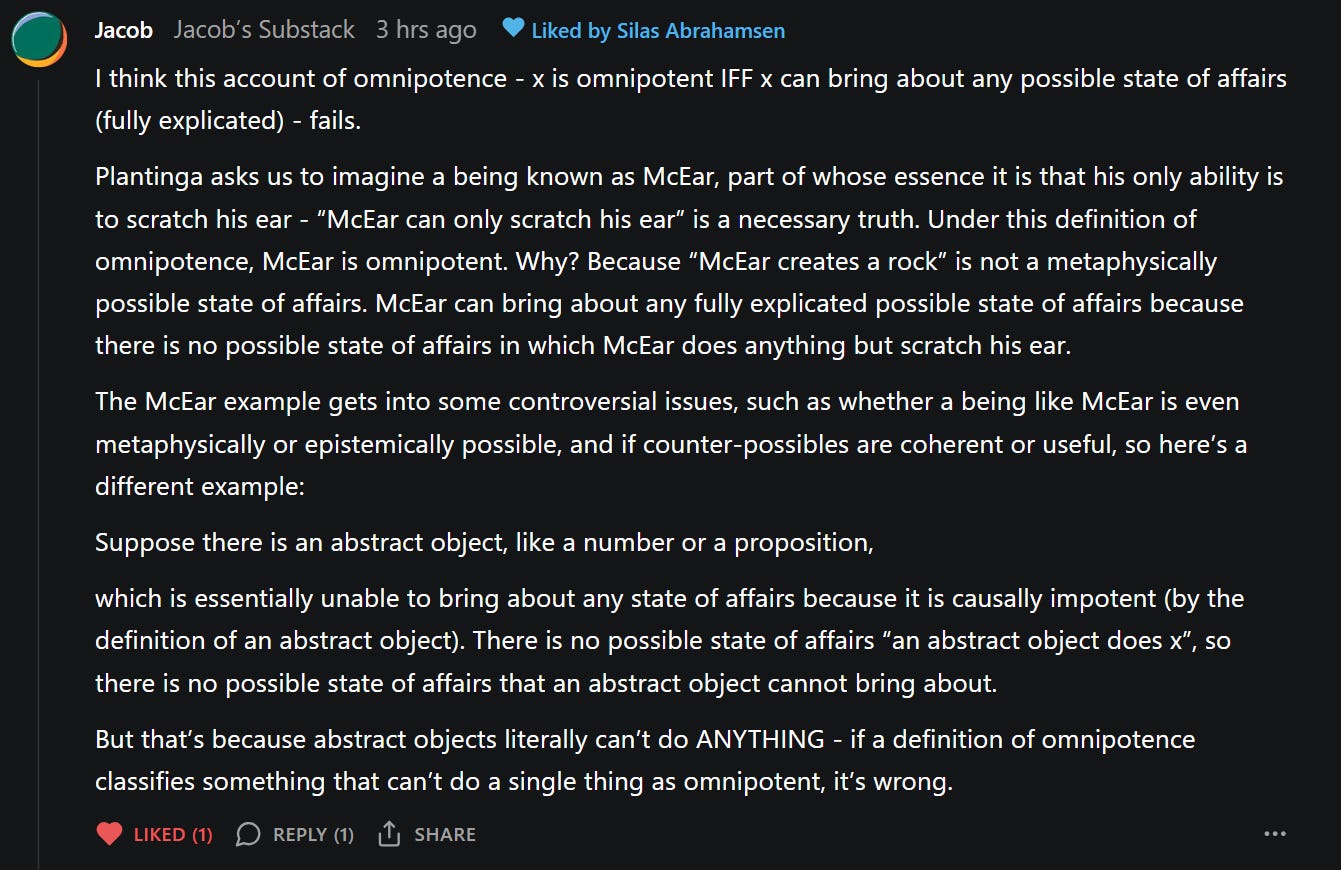

In my last post I tried to show that the omnipotence paradox fails. Turns out my argument fails. Jacob here pointed this out in a comment (this post goes out to you):

And it is even worse than what Jacob argues; on my account literally everything is omnipotent:

Take me as an example. I am actually omnipotent on my own account (very humble of me, I know). I am not strong enough to bench-press 500 kg right now (call right now time t). But that clearly means that I cannot bench-press 500 kg at time t. Now consider the state of affairs: “Silas bench-pressing 500 kg at time t”, that might be explicated to “a being which cannot bench-press 500 kg at time t bench-pressing 500kg at time t”, which is of course contradictory. So it is logically impossible for to bench-press 500 kg at time t. This of course applies to literally everything that I cannot do. And so I am omnipotent!

This obviously means that my definition is faulty, and so I haven’t solved the paradox. The most important goal of this post is just to flag that my previous post is inaccurate (I will also write a disclaimer in that post). But I also want to try to amend my previous account, so that it no longer clearly fails.

An Amended Definition

I have run through a few different possible amendments, all of which try to give some sort of more agent-neutral criterion, but it has been hard to hit the nail on the head. I think the following is the best I have done so far, but this time I won’t make the mistake of being overly confident in my proclamation. And so, here is a potentially adequate definition of omnipotence:

X is omnipotent IFF X can bring about any state of affairs, which it is possible for some possible agent to bring about, except those which it is impossible for X to bring about merely in virtue of their identity.

This is a bit of a mouthful, but I hope you will see that it is not too complicated once I explain it a little. Making “some possible agent” the criterion, instead of “possible states of affairs fully explicated”, makes it such that I am not omnipotent, even if it is logically possible for me to lift 500 kg, since there is at least some possible agent for which it is possible - so it basically makes the criterion more agent-neutral. At the same time it restricts omnipotence to not include things we would not want to include. So there is no possible agent which can make a round square, make water not be H2O, or make God not exist if he exists necessarily. And so omnipotence doesn’t require these things.

When I exclude states of affairs which are impossible in virtue of X’s identity, this introduces some agent-relativity, which will be necessary for omnipotence to be possible. To understand what I mean, it might be useful to take an example:

“A 500g rock, which it is impossible for God to lift, being lifted”

This state of affairs is clearly possible to bring about for some possible agent (assuming such a rock is possible) - I can lift a 500g rock. But into the state of affairs is stipulated that God cannot lift it, and so it is merely because God is “God” that he cannot lift it - it has nothing to do with what he is otherwise able to do. And so it shouldn’t infringe his omnipotence.

There might be a further question of whether such a state of affairs is even possible. I think that when we are describing a state of affairs, it is fair to say that we are intending our language to map on to reality in some way. But it is not clear what “A 500g rock, which it is impossible for God to lift” is really mapping on to - what feature of reality is it that makes it such that God cannot lift that rock? Is there just some strange metaphysical force which is stopping God from lifting it? What is really being brought into existence if God brings such a rock into existence, which differentiates it from a similar 500g rock without this feature? It seems much more like a combination of words which is perhaps meaningful, but which really fails to refer to anything in modal space.

So these sort of stipulated cases of weird objects are avoided with this addition to the definition, but as we will see shortly, this addition also avoids other problems, and so I think it is useful whether you think the above objects are possible or not.

It will maybe be in order that we take a quick look at the original omnipotence paradox, to make sure this definition still resolves it. So can God create a rock so heavy that he cannot lift it? Assuming we don’t mean the sort of strange case described above, this should be explicated to something like “Can God create a rock so heavy that no possible agent can bring it about that it is lifted?” Perhaps such a rock is impossible for some reason - I can’t really point to it, but perhaps there is one. Then God cannot bring it about, because it is impossible, and so no possible agent could bring it about. But that is also not really a strike against God, and is not inconsistent with the definition we gave. Maybe it is possible, and so some possible agent could bring it about - in that case God can bring it about. But then it is impossible that it be lifted by any possible agent by definition, and so it doesn’t seem like a limitation on his omnipotence that he cannot lift it - he would have to be impossible to be able to lift it, whatever that means.

Free Will

One potential counterexample to this sort of omnipotence is free will, if we take ourselves to have it. Consider the following state of affairs:

“Silas freely chooses to write an amazing blog post”

Even if we don’t have a definite conception of what free will is, we would probably all agree that God couldn’t bring this directly about - if he did, then it wouldn’t be my free choice, but just him forcing me to do it and God would just be the real author of the blog (something I wouldn't be surprised if you thought was the case already). God might of course indirectly bring it about, if he put me in certain circumstances where he knew it would happen (as is currently the case).

The reason is clearly that I have to bring it about for it to be my free choice. It should now be clear why the last part of the definition is useful. The only reason that God cannot bring the above about is that he is not me, but then that is just not relevant under our definition of omnipotence, since it is merely due to his identity that he cannot bring it about. This also doesn't seem like just an arbitrary caveat - it doesn't look like a restriction on God's power, when it is merely due to him not being me.

Omnibenevolence

I think the biggest problem with this definition of omnipotence is that it might be incompatible omnibenevolence. Consider the states of affairs:

“A person experiencing suffering with no good coming from it”

Or

“An innocent person being killed for no benefit”

Chances are you think at least one of these is bad. Furthermore it seems that most people can bring these states of affairs about, but it doesn't seem like God can, given that he is omnibenevolent. And so it may seem that omnipotence and omnibenevolence are incompatible (perhaps in conjunction with omniscience).

There are a couple of ways to respond here. One is to simply deny that these states of affairs are possible. An argument might go something like this:

God is necessarily existing and omnibenevolent. Furthermore, no world is brought about unless God brings it about. Since God is omnibenevolent, he wouldn't bring about a world where such states of affairs obtain, and so there is no possible world where such states obtain. Therefore there is no possible agent which brings such a state of affairs about, and thus it is no limitation on God's omnipotence that he cannot bring it about.

I must admit that this argument seems suspect. It feels sort of circular, but it is hard to put a finger on where it goes wrong (if it does). Furthermore there is just the problem that it screws up our reasons for acting morally, since we can be certain that any “immoral” act we perform will be outweighed, given this argument, and so we have no reason to not act immorally (at least prima facie). This last point is really a problem with certain theodicies generally, and not just here.

Another way out is to accept that God can bring such states of affairs about and still be omnibenevolent (perhaps by accepting my Divine Repugnant Conclusion). It should be clear how this removes the problem.

Although there might still be something agent-relative about acting immorally which still poses a problem. There seems to be something about morality which has to do with the mental states of the person performing the action. For example, it is immoral on some forms of consequentialism to choose an outcome which you expect to have a negative effect, even if it has a positive effect. This might be generalized to:

“A state of affairs, such that X believes it to be immoral to bring it about”

Where “X” refers to an agent. It might seem that it is possible for me to bring it about, since I can do something I believe to be bad. But God cannot bring about a state of affairs which he believes to be bad. And so God isn't omnipotent since there is something I can do which he cannot.

The problem here is that we aren't talking of the same state of affairs in the two cases. In the first case we substitute “X” for “Silas”, and in the second case we substitute “X” for “God”. But now it should be clear how this resolves. Both I and God can bring about states of affairs which I believe to be wrong. And neither me nor God can bring about a state of affairs which God thinks it is immoral to bring about.

There still seems to be something which we are not capturing however. Even if all the states of affairs I can bring about aren't in themselves immoral to bring about, there is still something about the way in which I bring them about which is something God cannot do - I can bring them about while thinking they are bad, and that makes it immoral to do, even if the state of affairs itself isn’t immoral to bring about.

The important thing here is to note that our definition is in terms of states of affairs, and not actions. It might feel like a limit on God's power that he cannot perform all the actions I can, but I don't think that it is. He can still bring about literally any state of affairs - any way the world could be, which I can (except things like me choosing freely of course), it is just that he cannot bring them about in the same way as I can. But that doesn't seem like a limit - it is also not a limit that God cannot flip a coin without knowing whether it will come up heads or tails.

Conclusion

I was certainly wrong about my definition in my last post (thanks Jacob). I have tried here to give an amended definition which gives an answer to the omnipotence paradox, while still being a plausible meaning for the word “omnipotence” and not failing in other cases. But I am not certain yet whether the definition I have given here is sufficient.

I have not thought about this for very long, so this could be a bit half baked, but here are some immediate intuitions I have.

I get uncomfortable with phrasings like "it is possible for some possible agent to bring about" if agent is taken to mean some subsystem of the universe subject to the laws of physics. As far as we know, the laws of physics are deterministic (modulo quantum randomness), so there is only one possible future quantum state, barring intervention into the laws of physics. But of course, god is presumably not subject to the laws of physics. God is fundamentally presumed not to be a subsystem of the universe. So I don't think we have to try to cook up a definition of omnipotence that covers both God and subsystems of the universe. In that case, could we not perhaps say that the omnipotence of God is the capability of God to change the laws of physics from one consistent set to another through a continuous process? Naively, this does not seem to run into paradoxes, unless the consistent laws of physics turn out to be unique, in which case omnipotence is trivial. If we think of a closed physical system as a universe, God could perhaps be conceptualized as the entity that decides what external sources gets turned on (in quantum field theory, an external source is equivalent to change in the laws). This also seems to avoid possible paradoxes involving concepts like 'immovable rock'. A continuous change in the consistent laws of physics might not allow such objects. Of course, I have to admit that "consistent" is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. The classical physicists definition of that would be something like "quantum mechanical, unitary" system. Should god be allowed to make time-evolution non-unitary? I don't know.

Of course, with the physicist's world view I have adopted here, I have more or less already ruled out free will, at least in the way I take that concept to be defined.

Thanks for an interesting post.

The problem at hand seems to be the result of the existing notion of possibility as an indexical. Every being is omnipotent, because each one of them cannot fail to bring about any state of affairs that is possible. I propose the following solution: 1 ) X is omnipotent if and only if X is capable of brining about any state that could be ever brought about by any individual entity 2) X can bring about any combination of the states possible to realize by all the entities that could have ever existed.

There is no possible being that would be capable of creating a rock possible to handle for it and at the same time not possible to handle.