While Soham is browsing the vegetables at the local market (Lidl), he catches a glimpse of his good old friend, Gordon, carrying a seemingly extremely heavy suitcase. Wishing to have a chat with his good friend, and curious why he’s carrying that monstrous bag around in a Lidl, he goes up to Gordon.

Soham: Hey, Gordon, good to see you!

Gordon: Soham, long time no see!

S: Look, we have a lot to catch up on, but let me just be upfront: Why in the world are you carrying that behemoth around in here? I mean, you hardly seem able to lift it.

G: Well, to explain it, will require a little detour, which might seem sort of irrelevant, but you’ll have to bear with me.

S: Of course! Go ahead.

G: As you probably know, I’m kind of big on Effective Altruism.

S: As one should be!

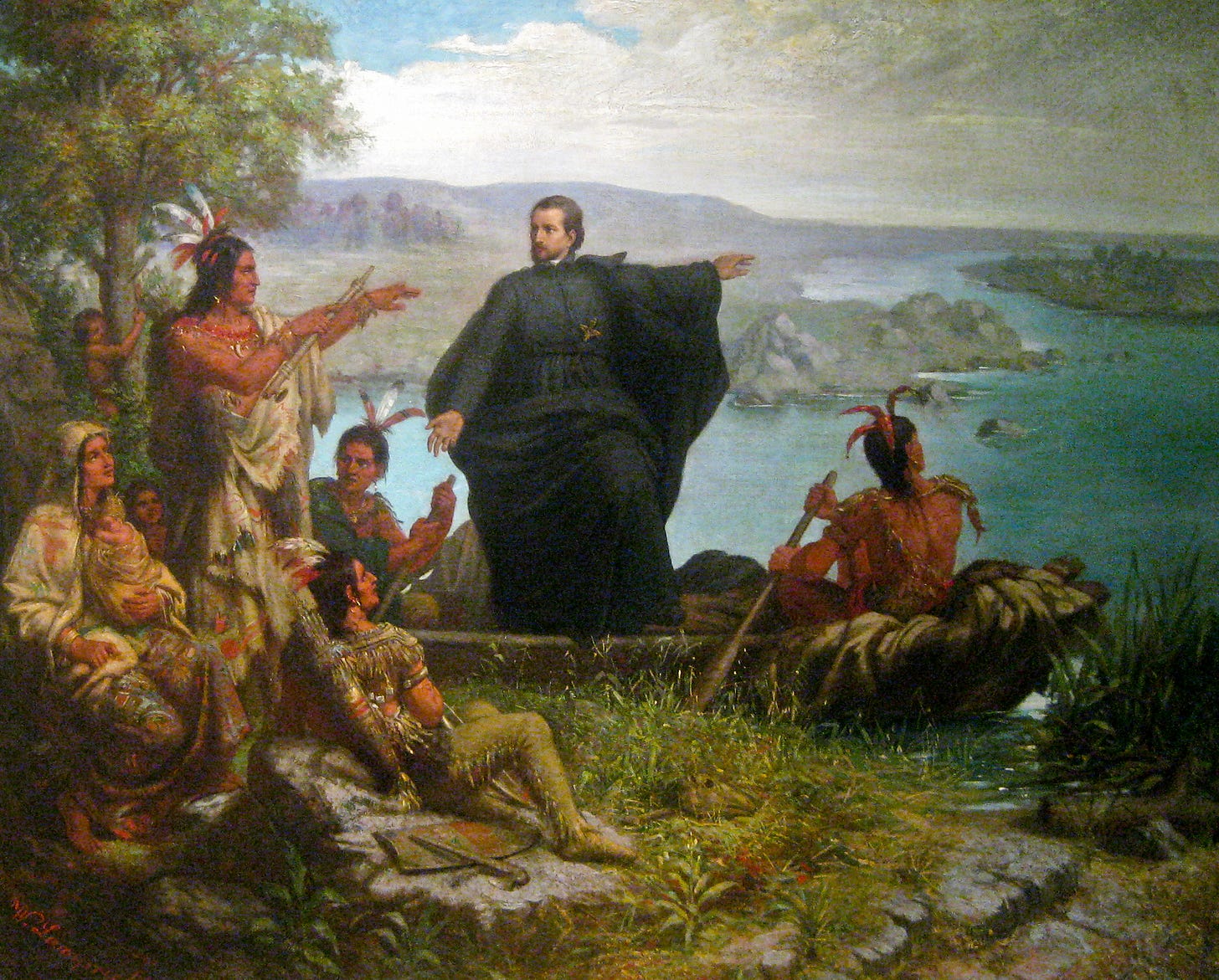

G: Exactly. So while browsing PhilPapers, I came across an article by Christian philosopher Eric Sampson, which argued that effective altruists should add evangelism to their list of causes. It’s really straightforward: Seeing as there are many non-stupid people who believe in views like Christianity, where having the wrong beliefs can lead a person to suffer infinitely negative consequences and vice versa, you should have a non-negligible credence in those views. But that means that you should have a non-negligible credence that, say, not confessing with your mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believing in your heart that God raised him from the dead, will lead you to suffer infinite negative utility—and likewise for other people. Using standard expected utility theory, even the slightest chance that some action of yours could cause someone to have the proper beliefs would then have infinite positive expected utility—you can save all the shrimp you want, but the effectiveness will pale in comparison to evangelizing effectively.

Even if you aren’t a fanatic when it comes to low probabilities, you should probably not be too confident that Christianity, or some other religion, is false, and if you really try your best, you will surely have a pretty high chance at saving at least one person throughout your life. And I must say, I found that article extremely convincing! All that is to say that the reason I have this extremely heavy suitcase is that I’m going on a flight to Gambia today, and I’ve packed my bags full of Bibles and copies of I Don't Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist along with malaria nets, which I’ll be distributing down there.

S: But what are you doing in Lidl then?

G: I obviously need some snacks for the trip! That reminds me, I have an extra ticket for the plane, and I know you’re really good at arguing. Why don’t you come with me, and then we can start an apologetics factory down there—perhaps call it “Catching Christians,” or something?

S: Dear Gordon, don’t you remember that I’m a universalist?; I think that all will be saved, so there’s no point in me going down there to try and “save” people myself.

G: Naturally I do, but that doesn’t matter. Surely you don’t have a non-zero credence in eternal conscious torment or annihilationism, right?

S: True, I don’t.

G: Then the case still goes through, since even if you think all will be saved, there’s a small chance they won’t, and you should try to minimize that risk for as many people as possible.

S: That might be right in my case, but aren’t you a committed atheist?

G: Yep, I think The God Delusion is a masterpiece of philosophy! Nevertheless, I’m still not 100% sure of atheism, and on the off-chance that I’m wrong, I would be exposing those around me to the risk of excruciating torment for all eternity. Since I’m a based fanatic about decision theory, I take that risk so seriously that it trumps all other finite considerations. But to reiterate, even if you’re not a fanatic, this should still be convincing to you, unless you’re unreasonably confident in no religion being true. Say that you have a 5% credence in Christianity. Surely you should be willing to make quite a big sacrifice for a 5% chance of, say, saving TREE(3) lives? Well, saving even a single person from damnation is infinitely more valuable than that, meaning you should be willing to sacrifice even more to do that! Anyways, I need to catch my flight soon. If you’re willing to follow me to the airport, I’d be happy to talk more—and maybe I can convince you to join me!

S: Of course, Gordon, though don’t get your hopes up!

Gordon puts his lentil chips and freeway cola on the conveyer, and the cashier gives him and Soham a puzzled look, as the two struggle to lift Frank Turek’s and complete works out of the store. They barely manage to lift the bag on the bus, with the help of 3 strangers, and continue their conversation.

Soham (panting): You could probably have guessed that I would raise this point, but there’s not just one religion that promises an eternal and infinitely good afterlife. I have a suspicion about how you might answer this.

Gordon (drenched in sweat): That's true, it would be foolish to think that Christianity is the only possible hypothesis that promises infinite negative or positive utility. It might at first be hard to see how to choose between different actions that have a chance of giving infinite value, since all such actions will have infinite expected value, and so might be thought to be equally good. To resolve this we might first consider a simple case: You are given the choice between a 99% chance of infinite value, or a 0.000001% chance of the same. Here you should clearly choose the former, even though the expected value is the same for both options.

It's not obvious what theory we should construct to give us this answer. One option might be to hold that the expected value really is the same for both options, but then add an additional principle for our decisions that says that when we have several options with infinite expected value, we should choose the one with the highest probability of giving infinite value—though this doesn’t work for cases where the values of outcomes only tend towards infinity, like the St. Petersburg game.

Alternatively, we might change the math to give us the result that the two options actually do have different expected values. One way of doing this is to introduce hyperreal or surreal numbers, which avoid the absorption property of infinites, and allow us to do transfinite arithmetic—though we might not have time to go into the details of this on this short bus ride.

Regardless of which underlying theory we use, however, I think it is quite clear how to answer your question: When considering different religions, I should try to get others to act in accordance with the religion I find most probable, and if some less probable religion doesn’t conflict with this, they should also act in accordance with this. So since I think protestant Christianity is most plausible, I should convince people of this—though it might still be good for them to confess every once in a while, in case Catholicism is true. There are some complications here if we opt for the mathematical response, since some religions might promise larger transfinite value than others, even if they are not as probable.

S: Very good! I wholly agree with the line of response, and this will be crucial for my point! Isn't it true, dear Glauc- I mean Gordon, that even a universalist will have to give some explanation for why God created the world?

G: Certainly Socra- uh, Soham.

S: And isn’t it also true that, since there is immense suffering in our universe, the reason a good God would have, would be if some greater good could be achieved through a temporary existence on earth, which could not be acquired by a merely heavenly existence.

G: Nothing could be more plain!

S: Now, Gordon, tell me which would be the better thing for a good God to do: to bring about a merely finite greater good from an earthly life, or bring about an infinite greater good from it?

G: The infinite greater good would be better, to be sure.

S: Exactly. So from this we can be certain that if it is possible for God to bring about infinite good from a finite life on earth, he would do this.

G: There can be no doubt about it.

S: Good. The question now becomes what reason God has for putting humans on earth. This is not very clear, though I think a quite plausible answer is that we are put on earth in order to form meaningful bonds with each other. After all, the reason will surely have to be some good that derives from genuine suffering, as it’s otherwise unclear why God would allow suffering in the world. More specifically, it seems like the bonds that are salient given suffering are those formed when we help each other overcome and avoid suffering, i.e., when we act morally towards each other. This may seem a bit ad hoc, but I think it becomes more plausible when we consider why God would give us a moral sense (assuming our sense of morality really is a truth-tracking one, given by God). After all, what reason could God have for giving us such a sense, except for if the point is that he wants us to act morally.

So now we must ask whether it is possible for God, given universalism, to bring about infinite good from our life on earth. The relevant sort of probability here is clearly epistemic probability, seeing as we’re talking about decision theory. With this in mind, it seems clearly possible—and in fact highly probable—that he would be able to do this. Just as a sketch for a possibility, it might be that we have perfect memory in the afterlife, and the bonds we form on earth give us a special sort of value for the infinite duration of the afterlife.

This story doesn’t have to be true or particularly plausible, it simply has to be probably not impossible, given universalism. If what I have argued is right, then so long as I think universalism plus some story along the lines I have sketched is more plausible than eternal conscious torment or annihilationism combined, I should just try to act morally on earth, rather than convince people of some religion (though having a relationship with God while on earth might of course also be a great good I ought to take into consideration). Likewise if you, Gordon, have similar credences to me, conditional on theism, then you should focus on helping people here on earth, rather than send them off to heaven.

G: Very interesting, Soham, though I fear that you are missing something. Even if acting morally might provide infinite value, given universalism, it still seems like eternal conscious torment or annihilationism offer greater transfinite value. It might be that having a valuable relationship for eternity will provide infinite value overall, but it will only give a certain amount of value each day, and the difference in value between having such a relationship and not having it will surely be less than the difference between spending a day in heaven vs. a day in hell.

As an analogy you might imagine standing before two buttons. The first will give you 1 util a day for eternity, while the other will give you 1000 utils a day for eternity. While both will certainly give you infinite value, you should clearly prefer the latter, so there’s a clear sense in which it will give you more value. While we would need the more advanced math to describe this rigorously, I’m sure you can see the problem clearly enough on an intuitive level.

S: That’s certainly a good point. Would be possible for God to provide as much value through universalist values, as through eternal conscious torment? On the face of it, I guess I just don’t see why he shouldn’t be able to. We might for example imagine that a life in heaven is close to neutral without these valuable relationships forged on earth, and each relationship gives an immense amount of value each day in proportion to how much the people helped each other on earth. So long as a story like this would give as much value as eternal conscious torment, while being more plausible than it, then my earlier argument seems to go through.

In fact, if you find the intuitions behind universalism plausible, I think you have a good reason to suspect that universalism will always dominate. After all, if you find universalism plausible, it’s presumably because you think it would be wrong for God to punish people for not believing in him. If this is right, then it seems like you should have a lower credence in ECT views in proportion to how much God punishes people on them, such that there will be an inverse relationship with how bad it would be for a person to not believe in God and how probable it is that they would suffer this harm.

On the other hand if universalism is true, the reason that God creates earth is, with some decent probability, that it brings about some good related to acting morally in the face of suffering. Now, the greater the good brought about from this, the stronger reason God would have to create the physical universe, such that there’s a positive relationship between the probability of God creating the world and the good gotten from acting morally in the world.

Hence while a theory of ECT is made less probable the greater the impact of getting people to believe, a universalist theory is made more probable the greater the impact of acting morally. All taken together, this means that a person with universalist intuitions should be pretty confident that it’s better to just act morally—i.e. give to effective charities, etc.—than to try and convince people of Christianity.

G: As you’re speaking, you make it sound compelling, but I can’t help but suspect that the motivation for this is that it’s convenient, rather than that it’s actually more plausible. It’s super hard to imagine how good or bad different possible afterlives might be, and I’m frankly not sure whether I can judge what it’s possible for God to bring about from the suffering and relationships on earth. So I’m just very skeptical that I should have much confidence in your argument, especially given how prone I am to believing it for non-rational reasons.

S: Some of your your uncomfort—can you say that?—might just be because the theories we’re talking about are such a small proportion of your credence-range. You think ECT and universalism are both incredibly unlikely, and when that’s so, what sounds more plausible might just be informed more by what depictions you’ve seen in pop-culture than what you should actually think is more plausible. I too find it a little too convenient, which gives me some higher-order doubts, but I also genuinely do find the argument pretty compelling. Additionally, being very unsure about the probabilities should also just make you not-super-confident that God couldn’t bring unimaginable good from relationships formed on earth.

The more we talk, the more I also fear that we’re just getting the decision-theory wrong altogether! I mean, when all considerations but those informed by the tiniest sliver of your credences are swamped, then we’ve surely just gone wrong somewhere! Right?

G: Well, this is definitely an implausible cost of taking the hard expected value line—but no one gets out unscathed in decision-theory, and especially not when we’re considering infinities. I still think that denying EV will involve biting bullets larger than this, so I’m not too-too worried.

In any case, it sadly seems we’ve reached the airport, so I’ll have to get off now so I don’t miss my flight. I’m happy I met you before going, and I hope you’ll come and visit me at some point! Goodbye!

S: Likewise, I’m glad I got the opportunity to say goodbye, and I hope I’ve convinced you to at least do some humanitarian work while you’re down there.

With that, the two parted ways; Soham going home, and Gordon going to start a new life. Rather Gordon would have started a new life in Gambia if it weren’t for the fact that the sheer weight of his bag meant it would’ve costed $51,957 to bring on board. He thus decided to cut his losses and go home as well.

You Might Also Like:

Is there a sense in which this argument proves too much? Like, traditionally, evangelism doesn’t involve murder because God said that murder is bad. But if we’re going full-bore infinite-utilitarian about all this, is there a sense in which any extra time in heaven is infinitely valuable, and outweighs the nastiness of killing?

Presumably for the same reason we should prefer a 99% chance of infinite value to a 1% chance, we should prefer infinitely-awesome experience for 99 days to 1 day. I don’t know how to make that math work out, but if it does, then it seems like a truly effective missionary would find himself committed to murdering those he’s converted, no?

Imagine Gorgia..er...George accepts some aspect of Pascal's Wager, and furthermore is confident that some Armenian Protestant Christianity is the ticket to heaven, i.e., infinite expected positive utility. It's also the case that George really loves the never-ending parties at the Temple of Dionysus (best sex, wine, and entertainment in the world, as far as he's concerned). And we are already assuming doxastic voluntarism; therefore, George can freely choose to commit to the creed of Protestant Christianity at any point, and secure his spot in heaven. In fact, as long as George commits to this creed before he dies and remains in the faith, he will go to heaven, regardless of what he did and believed before committing himself to the Protestant faith.

In other words, he has a finite but very large number of opportunities to commit to the correct faith that secures himself a spot in heaven, for he will surely die at some point that he cannot predict. George is a reasonable person and would like to maximize utility. His strategy is to enjoy the heck out of the parties at the Temple of Dionysus as long as he can, and then repent and commit to the Protestant faith. So each day when George wakes up, hung over at the Temple of Dionysus, he reasons as follows: "No matter what I chose today, my expected utility will be the same whether I repent now or wait until tomorrow, since I have good reason to believe there will be a tomorrow. So I am indifferent, at this moment, between choosing sin and choosing salvation, or maybe slightly more in favor of more parties." And so George carries on, living a life of sin at the Temple of Dionysus, every day, until his mate Alexander trips on lute, knocking a marble plinth onto a passed out George, killing him. George never repents and therefore never goes to heaven.

Has George exhibited a failure of rationality? It depends on George's ability to set an intention and stick to it, which in turn depends on whether George presumes that the norms of rationality will be constant for his infinite future self. If George accepts irreducibly global norms of rationality, then his choice to squeeze in some more parties is irrational, even though any individual decision to stay at the never-ending party is seemingly rational. What this illustrates is that to set an intention for an infinite future requires a belief that the norms of rationality will remain constant into the infinite future, and in every setting, and that his future self will value heaven just as much today as it will in a trillion millennia. But is it rational to believe that? It seems under-determined, to me.