Better to Have Been

Against David Benatar's asymmetry

This week I’m simply sharing an essay I had to write for one of my courses. The assignment here was specifically to respond to David Benatar’s “Why It Is Better Never to Come into Existence.” Due to it being much shorter than his later book, this probably won’t address many of the points he made there. But because there was a pretty tight size-restrictions on this essay, and because I’m not reading a whole book for this, I’m just addressing what he writes in the article. Likewise, you might notice a lack of general hilarity otherwise characteristic of my writing, but this is again due to it being an assignment, though it’s hopefully weighed up by tighter writing and argumentation than usual. Anyways, enjoy:

1. Introduction

Something many consider to be one of their greatest purposes in life is to bring children into the world. In addition to being a popular goal, it also seems morally unproblematic in most cases—what could be wrong with it? In his article “Why It Is Better Never to Come into Existence,” David Benatar (1997) argues that it is not as innocent as it first might appear. His main argument for this is that there is an asymmetry between pleasure and pain that makes nonexistence either equal to or preferable to existence in all cases. This asymmetry, Benatar argues, is the best explanation for a number of intuitive and popular views. My thesis is that our intuitive views are better and more elegantly explained without Benatar’s asymmetry than with it.

In section 2 I will explain the structure of Benatar's asymmetry and how it implies that it is always just as good or better not to come into existence. In section 3 I present the three “data points” that the asymmetry is supposed to explain, and argue that these can be explained better and more elegantly without the asymmetry, hence why it should be denied.

2. The structure of Benatar's argument

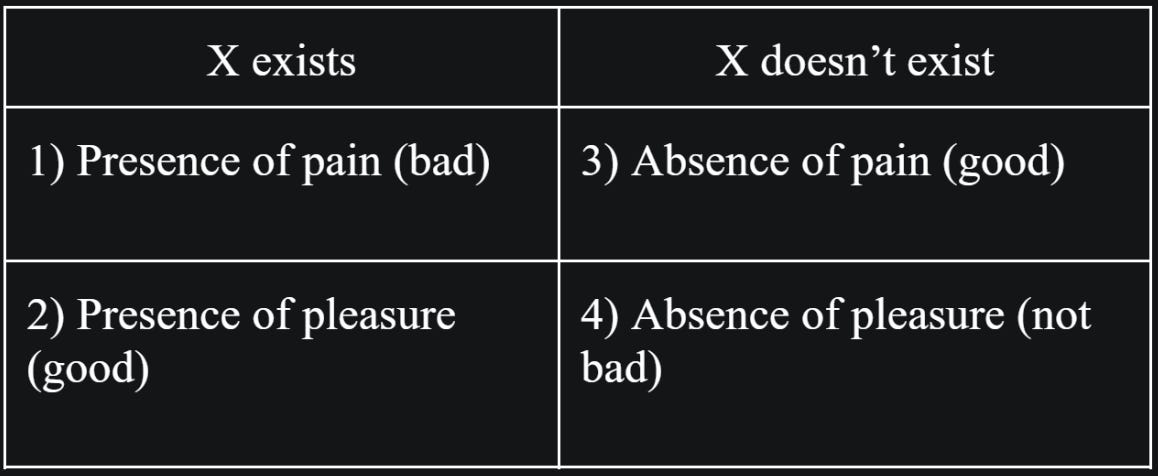

Benatar's argument is based on an asymmetry between pain and pleasure. Whereas the presence of pain and pleasure are respectively bad and good, the absence of pain is good even if this good is not enjoyed by anyone, but the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone for whom the absence is a deprivation. This can be represented in a matrix:

It should be noted here that Benatar has a somewhat idiosyncratic jargon, as he means “good” and “bad” in a relational sense rather than intrinsically (Benatar, 2013, p. 128). It is thus not that the absence of pain in itself is good, rather it is simply better than its presence and vice versa. Likewise, “Not bad” should be understood as “not worse than (2).” It is now clear how the argument works: Looking at it in rows, we see that (1) ≤ (3) and (2) ≯ (4). This means that there are no cases where the left column has an advantage over the right, but many cases where the right column has an advantage over the left—in particular, all except the set of special cases where X never experiences any kind of pain—and it is therefore always better, or just as good, not to exist.

It should be mentioned here that the use of pleasure and pain specifically is not necessary for the argument to work—if you are a non-hedonist, you can instead insert whatever you think has moral value and repeat the argument.

3. The asymmetry is not the best explanation

Benatar's main argument for the asymmetry is that it provides the best explanation for three widely held views:

We have a duty not to have suffering children, but no corresponding duty to have happy children—since it is bad for a person to come into existence, we may have a duty against this, but since it is not bad (often even good) for a person not to come into existence, we have no duty to avoid this (i.e., no duty to have children).

We do not use as a reason for having children that it benefits the child, but we sometimes use as a reason for not having children that it would otherwise harm the child—since it is at no point beneficial for the child to come into existence, this cannot be a reason for having children, but since it may be bad for the child to come into existence, this can be a reason for not having children.

We can regret on behalf of a suffering person that they came into existence, but we don’t regret on behalf of potentially happy non-existent persons that they did not come into existence—since it may be bad for a person to come into existence, we can be upset about this, but since there is no advantage to having a positive life over not coming into existence, we cannot be upset about the lack of this.

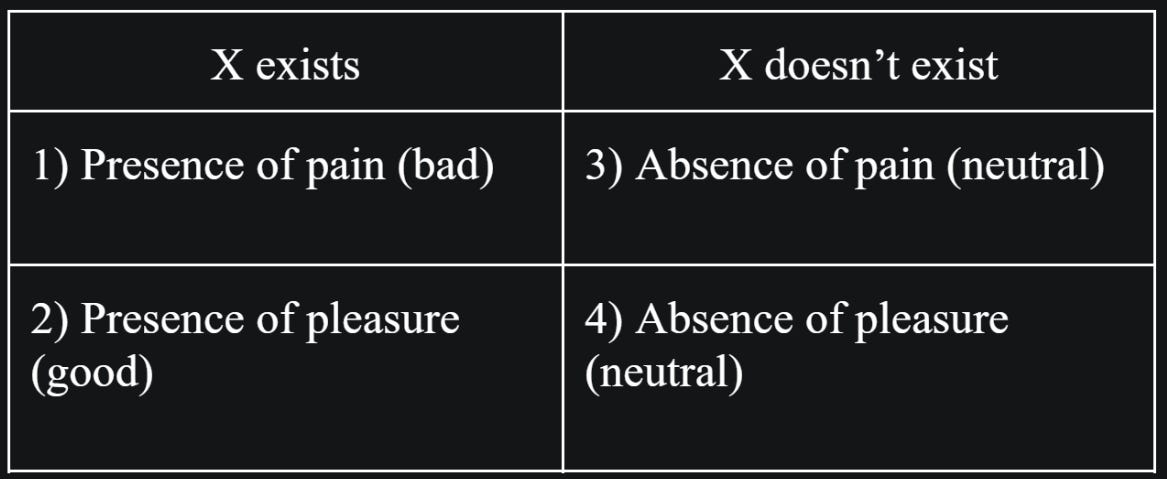

Since this is a kind of inference to the best explanation, one possible way to refute this argument would be to provide a better explanation of the three points—or at least show that there is nothing notable to be explained. This is the approach I will use here. As an alternative to Benatar's matrix, I will use the following (here “neutral” should be understood as no valence; zero units of utility):

In Benatar's jargon (3) could be called “bad” and (4) “good,” but as he himself mentions (1997, p. 347) , this gives the impression that it is somehow inherently bad if a potential child does not come into existence. But this is of course not the case, it would simply have been better for the child if it had come into existence, but non-existence is in itself neutral. Benatar's use of language here seems to be more confusing than helpful, and I will therefore use these terms instead.

This symmetry seems to be the most natural and widely intuitive way to look at the relationship between existence and non-existence in relation to pain and pleasure. It is therefore doesn’t seem unreasonable to assume that this has an advantage, all else being equal (although this is not essential to my argument). All else is of course not equal, Benatar would argue, as there are 3 points to be explained.

Point 1 of Benatar's argument seems relatively straightforward to explain for non-consequentialists (especially deontologists), since there will often be actions that do not produce the best consequences, but which will not be wrong. We can compare this with a similar example: If you have a child, there seems to be a duty not to leave it to starve. But if you do not have a child, there seems to be no corresponding (or correspondingly strong) duty to adopt a starving child. It is completely unnecessary here to posit some kind of axiological (i.e. concerning good and bad) asymmetry, in order to explain the deontic (i.e. concerning duties) asymmetry—indeed, it would seem absurd to say that it is less bad for a child to starve if we haven’t done anything than if we have done something. The deontic asymmetry can be explained with theoretical tools that non-consequentialists already have, and the same tools can be used in exactly the same way when it comes to having children, and here again it seems like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut if we use an axiological asymmetry to explain this.

Consequentialists can also apply their answer to the above example to the example of having children. Perhaps for practical reasons we must live as if we do not have this demanding duty, perhaps there must be room for a degree of supererogation in our theory, or perhaps we do in fact have this duty. It is old news that consequentialism can be very demanding, and so it is not surprising in this case either, and there is no need to invent new and counterintuitive solutions to old problems.

Benatar (1997, p. 346) responds that even among people who believe we have positive duties (e.g., consequentialists), most do not believe we have a positive duty to have children. Even assuming this is correct, there may be several different explanations for this. First, other positive duties seem less demanding—donating, say, 10% of your income per month to charity seems less demanding than spending a large portion of your life raising a child. It may also be that other duties trump this one—you could probably do more good by spending the time it takes to raise a child earning more money for charity. Finally, it may simply be that many who accept positive duties have not considered this case in sufficient depth.

It is more difficult to reconcile point 2 with the symmetry between pain and pleasure—even if one believes that the goodness of an action is not sufficient to oblige us to do it, one would probably still believe that its goodness gives us at least a small reason to do it. This attitude is therefore incompatible with the idea that it should be good to have a child with a good life in the same way that it is bad to have a child with a bad life (in a purely axiological and not deontic sense), which is implied by the axiological symmetry. I will thus not attempt to reconcile these, but simply question the extent to which this point should be respected.

First, it is not clear that this is actually a particularly widespread attitude. Anecdotally, “you would be such a good parent” is not an unheard-of response to someone who doesn’t want children (implicitly understood that a reason for having a child is that it would be good for the child to have such a good parent). There may be a tendency to downplay the importance of the happiness of potential children in the same way that there may be a tendency to downplay the importance of the happiness of children who are very far away, relative to children who are close to us. However, this does not seem to be because we actually believe that this is less important, but simply because it is not something we have in mind in everyday life. Moreover, this intuitive axiological judgment is likely to be influenced by the asymmetry of duties we discussed above—if we do not have as strong a duty to help children far away as to not harm children close by, we may come to no longer take the pain of children far away into account as much when it is not caused by us. But this is not because we actually believe that the pain of a child far away is less bad for them, it is simply because in our intuitive and unreflective moments we may tend to mix up axiology and deontology.

Second, it is just a sad fact of moral theory that some of our intuitive views will almost certainly be incompatible. For example, it is both intuitive that an ideal observer would morally prefer one person to be murdered than two people to be murdered; that if an ideal observer morally prefers us to take an action, it is not wrong to do it; and that it is wrong to murder one person to save two (ceteris paribus for all three). When these conflicts arise, we must find some kind of reflective equilibrium by sorting out the inconsistencies and assessing which considerations weigh most heavily. With the error theory I have given in the previous section, as well as the other arguments in this article, my hope is that the weight will end up against this point and in favor of axiological symmetry.

Finally, Benatar seems to be making the wrong comparison in point 3. It is true that we can regret on behalf of a suffering person that they were born, and that we do not regret on behalf of a potentially happy person who was not born. But here we are comparing a non-existent person to an existing person, so it is clear that there will be an asymmetry in our retrospective judgments—we should instead be comparing existing to existing and vice versa.

Just as we cannot regret that a potentially happy person does not exist, we do not seem to be happy that a potentially suffering person does not exist. As a possible counterexample, we might be happy if a terrible mother turns out not to be pregnant, after we had thought she was. But here we must be careful not to misuse our language. A similar example is that you are driving on a frozen highway, where your wheels start to slip and you skid. But after a few seconds you manage to straighten out and you avoid crashing. Here you are similarly “happy” that you did not crash, but a better description would probably be that you are relieved about it. Before you started to skid, you were in exactly the same situation as you are now, and it would seem strange to be happy that you are not about to crash every second you drive. The fact that you did not crash is not in itself good, but you simply avoided something bad happening. If one insists on using the word “happy,” we can simply say that this word does not indicate that what we are happy about is better than nothing—definitions should not be what separates us.

On the existing side, just as we can regret a suffering person existing, we can be happy about a happy person existing. For example, I am happy to exist. Likewise, I am happy for many of my family and friends that they exist. I can also be happy for those people who have extraordinarily smooth and successful lives that they exist (e.g., those who are very rich and never experience significant losses). None of these attitudes seem psychologically impossible (I do have them) or irrational and absurd; in fact, they seem completely ordinary, normal, and understandable. So there is not clearly the asymmetry in retrospective attitudes that Benatar claims.

Seeing as Benatar's argument is based on widely held attitudes, it is worth mentioning another one: that it is not bad for a person with a good life to come into existence. This is directly incompatible with the asymmetry, and very plausible. Here we begin to approach something like a Moorean shift. Benatar gives something like the following argument:

If the asymmetry is correct, it is always bad to come into existence.

The asymmetry is correct.

So it is always bad to come into existence.

I can now give a reverse argument:

If the asymmetry is correct, it is always bad to come into existence.

It's not always bad to come into existence.

So the asymmetry is not correct.

The question here is whether (2) is more plausible than (5). If so, we should accept (3) and if not, we should accept (6). The previous work has been to undermine the justification for (2). Since (5) itself seems very intuitive, this seems apparently sufficient to reject (3). But to drive home the point, we can, in support of (5), imagine Doris living 1000 years of the most perfect life imaginable—whether that involves having nice conversations with friends, or consuming crack cocaine in a steady stream. The flip side of this arrangement is that at one point her nose itches for 1 second (perhaps she even gets pricked with a needle). Despite this, it seems obvious that it is not bad for Doris that she has come into existence—that it is good, in fact. To further press this point, we can imagine that Doris has already existed for a millisecond, after which she is given the choice between living the 1000 years with a little pain, or ceasing to exist. Here it is clear that Doris would prefer the former. But whether she has already existed for a millisecond or not does not seem to have much bearing on whether it is good for her to experience these 1000 years.

In fact, (5) can be supported by 3 points that mirror Benatar's: 1) We do not have a duty not to have children with good lives, 2) although it may be a reason not to have children that they are harmed by it, we often judge that the good in their lives outweighs this, and 3) we do not regret that people with good lives come into existence. While axiological symmetry can explain Benatar's 3 points without major problems, it is far from clear how asymmetry can explain these 3. But to focus only on Benatar's points is to ignore at least half of the data that needs explaining. An explanation is only the best if it best explains all the data, and when we look at the total data, it suddenly seems clear that axiological symmetry is preferable to asymmetry.

4. Conclusion

Our intuitive views are thus better and more elegantly explained without Benatar's asymmetry than with it; most of the points Benatar mentions can already be explained with resources available to less radical theories, and what cannot be explained with this seems to be offset by conflicting considerations. It is of course natural that the strengths of these different considerations rely on our axiological and deontic intuitions. Whether these arguments are convincing will therefore—at least in some respects—depend on the extent to which the reader's basic intuitions agree with my own. But, as with Benatar, it seems to me that the views I have advanced here are very widespread, and if what I have said is correct, the best way to reconcile these views is to reject Benatar's asymmetry and accept a symmetry between pleasure and pain. Finally, it should be mentioned that a rejection of the asymmetry is not incompatible with antinatalism more generally. For example, one could accept a kind of de facto antinatalism that claims that the vast majority—if not all—of real-world lives contain a preponderance of pain, such that it is generally bad to enter into existence. This is fully compatible with the symmetry between pleasure and pain.

References

Benatar, D. (1997). Why It Is Better Never to Come into Existence. American Philosophical Quarterly , 34 (3), 345–355.

Benatar, D. (2013). Still Better Never to Have Been: A Reply to (More of) My Critics. The Journal of Ethics , 17 (1), 121–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-012-9133-7

You didn't exist, and yet you still came to exist. This is true for everyone that ever lived and will live, and it demolishes the idea that not existing is better. How can not existing be better if it isn't capable of stopping a life from being imposed? You didn't exist, yet a life was still imposed. So, had you never been born, then some *other* life would have done "the imposition*. Lives are born all the time. And so: If it isn't one life it's another. There's no escaping one life or another from being imposed, because when you don't exist, there's no you to escape one imposition or another... Just as you were not able to avoid *this life from being imposed (*the biological life that's reading this right now).

The four allegedly widely-held beliefs that Benatar cites in support of axiological asymmetry seem jointly less plausible/intuitive to me than his radical conclusion is implausible/counterintuitive.

Since I hold onto the rule that rationality doesn’t permit us to employ non-obvious premises as a means to justify deeply controversial conclusions, the asymmetry argument is (and will remain) thoroughly unconvincing to me.